Interactive visualization of the history of the latin alphabet, showing the temporal and formal relationships of the different scripts and typefaces to each other

Culture Society Technology

Image source: Wikimedia

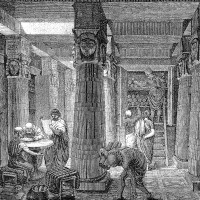

Image source: Zeichnung von O. Von Corven

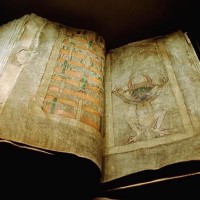

Image source: Wikimedia / Kungl. biblioteket

Image source: Wikimedia User Marcok CC BY-SA

Image source: Wikimedia / Cleveland Museum of Art

Image source: Wikimedia - User Beckstet

Image source: Wikimedia

Technology

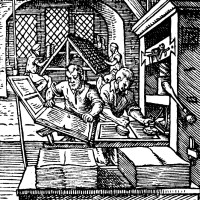

1200: Paper production in Europe. Paper was invented in China as early as 140 AD and reached Europe via the Indian and Arab cultures. Since it is significantly cheaper and more available than parchment, it becomes established as a writing medium from the 14th century onwards.

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikipedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Wikimedia

Image source: Marcin Wichary CC BY 2.0

Image source: Screenshot

Read the original article

Comments

By WillAdams 2025-06-193:34 F.W. Goudy has a nice bit in one of his books where it is shown how the lowercase _g_ developed from the uppercase --- I also have a photocopy of page from a calligraphy text where it advocates for using the older script forms for headings, more recent for subheads, and then setting body text in current/recent styles, using age as a guide to hierarchy, which I've done for a couple of projects and it can have a nice effect.

Why do Ç, å, é, etc. exist? Why didn't people come up with new characters? Why use "sh" and "ch" instead of making a new character for those sounds? (Maybe other languages do this but English doesn't).

In Spanish, we consider Ñ to be a different letter, with its key in keyboards and under a different chapter in dictionaries. Of course you could say that it's just an N with a ~. But that tilde is not defined for any other letter. Why did they do it? In medieval Spanish it was common to write two Ns in many words, with a different sound. For example: "anno", which is now: "año" (year). Two Ns was very similar to M so the tilde was added to remark that it was two Ns, not one M. Later, they just wrote one N with the tilde.

Never learned Spanish, so I did not know this! But it makes sense, just like in German: ß is ss, ä is ae, ö is oe, and ü is ue.

By weinzierl 2025-06-1923:01 Exactly and ä is never just a, ö never just o and ü never just u. Words like "Uber" just feel wrong from a German perspective.

Also, ß is ss and since words don't start with Ss there is no need for an uppercase ß. When whole words are capitalized ß turns into SS.

Of course there is a little edge case where capitalization isn't reversible. For example, is the capitalized version of the name MASSMANN to be converted to Maßmann or Massmann? That is in my opinion the only reason the uppercase ß was added to Unicode. To resolve this ambiguity. It has no place in proper German typography.

By naikrovek 2025-06-1921:06 I can’t tell if that’s lazy or if using a new character instead of two unadorned vowels is inventive.

Like all things I don’t understand, I suspect fashion was heavily involved when the decision was made.

By cryptonector 2025-06-205:281 reply Worse, in Spanish it used to be that 'll' and 'ch' were until recently digraphs considered separate letters, which meant that they would sort as such too. That is incredibly annoying to implement.

By jillesvangurp 2025-06-207:471 reply Technically the ij is a digraph and sometimes a ligature. Although computer keyboards have never really supported that but some mechanical keyboards for typewriters used to. Most modern Dutch people would simply be typing an I and a J and wouldn't necessarily know that they need to also capitalize the J at the beginning of a sentence (Ij would be incorrect). Not a lot of words start with that but some place names do.

The Dutch keyboard layout is effectively US international. There are no special characters that that keyboard supports; including all the accents/modifiers we inherited from French, German, etc. Spelling without those is now correct.

This is something that has evolved over the last decades. In the eighties, people would memorize the character codes to produce letters with those. I remember having a card with the right key combinations for word perfect. This is not a thing anymore. People just skip it and the grammar and spelling rules were actually modified to not require these anymore in most situations.

Funnily enough, the Y, is not commonly used in Dutch and usually referred to as the Greek IJ but pronounced the same way.

By cryptonector 2025-06-2017:17 For me the Unix/Linux compose key and compose key sequences is where it's at. It's much nicer than the US international keyboard input method, though if I were constantly typing in a language that requires [lots of] accents/diacritics I might have to switch.

By dragonwriter 2025-06-1916:17 And, while its not the case any more, but illustrates how arbitrary the "new letter" vs. "new sound for old letter or combination" is "ll" also was considered its own letter for ~250 years.

It seems a bit of an arbitrary choice. For example, Polish has digraphs, but Czech has diacritics, and Icelandic has a couple of additional letters that aren't modified Latin letters.

Old English had four letters that are not in today's US-ASCII, two of which are borrowed from a runic alphabet rather than created by modifying Latin letters.

It's also a bit arbitrary whether a modified Latin letter is regarded as a new character or an existing character modified by a diacritic: take Ø, for example. And there are characters like Æ. And never forget what Turkish did: add dotless i so that ordinary i could then be regarded as dotless i plus a diacritic (though of course it isn't usually regarded that way).

Slavic languages originally used the very unique Glagolitic script, developed by saints Cyril and Methodius. However, their disciples later created an alternative Greek-based script, which eventually prevailed.

My guess is that the educated people of the time were very familiar with Greek, so it was easier for them to work with Greek letters rather than the newly invented ones. It probably was the same for Latin-based scripts as well.

By mananaysiempre 2025-06-1914:271 reply Worth remembering that all of the people you mention were Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox monks and missionaries, so for them Greek was both the international vernacular and geographically close.

By userulluipeste 2025-06-1923:32 Cyril and Methodius were in fact Greek Christians, baptized as Constantine and Michael. They only later adopted monk names that they are ultimately remembered as. Now, considering that the Byzantines (or "Eastern Romans") were in conflict with Slavs since long before the brothers were born, it's unlikely for their family to be of Slavic background and at the same time for their father to be in a prominent military position (droungarios).

The script that came to be known as Cyrilic was developed by Cyril and Methodius' followers, after they were exiled from Great Moravia (by the bishop that replaced Methodius), so it's safe to assume that those in that group were not Bulgarians either.

The timeline starts with 22 characters for Capitalis Monumentalis and ends with 26 characters in upper and lower case each for Sans-Serif. People did come up with new characters (JKUW), you're simply used to them.

By adrian_b 2025-06-199:58 There has never been a 22-character Latin alphabet.

The original Latin alphabet had 21 letters. Then G has replaced Z, without changing the number of letters. Then, by the time of the Empire, Y and Z have been added at the end (the same Z that had been removed earlier, while Y had the same origin as V, but by this time it had acquired a distinct pronunciation in Greek).

Then the Latin alphabet had 23 letters for more than 1000 years.

It has grown to 26 letters during the Middle Ages, with the addition of J, U and W ("u" was originally the small letter form of "V"; distinct letters U and V have been created by making a capital "U" and a small "v").

In the case of K, U, and W, those were borrowed from Greek, weren't they?

Not sure where J came from.

One question is why we borrowed K when we already had C. In modern English, C is more or less a completely superfluous letter, adding unnecessary complexity to pronunciation. Seeing my son try to pronounce "cycle" is one of many examples.

By ryao 2025-06-198:55 The Latin alphabet was based on the Etruscan alphabet, which was based on the Greek alphabet, which was based on the Phoenician alphabet. In early Latin, C, G and K were all pronounced the same way. They later dropped G, only to bring it back when they realized that they used C to refer to two different consonants, and wanted to disambiguate them. They assigned the less common constant to G.

J was introduced because I had a similar problem, except I could be either a consonant or a vowel, rather than any of two consonants. The same applied to the introduction of U for V. Well, almost the same. In the case of I, they added J to be the consonant, while in the case of V, they added U to be the vowel.

Finally, people changed the pronunciation of V over time to be something new, and W was introduced to be the original sound in English. W does not exist in Latin since V fulfills its role, unless you are using a modern pronunciation that changes how V is pronounced and then you still do not need W. There were other sound changes (see Italian), but this is sufficient to explain all of the letters. Well, there is also Z, which they removed from early Latin and later reintroduced to represent a Greek sound.

All the Latin letters, except for G, which is a modified Greek letter invented by a Roman, come from the Greek alphabet, only at different times.

The original Latin alphabet had 21 letters:

ABCDE FZHIK LMNOP QRSTV X

The letter V (Greek u-psilon) was used to write the sound U, both as vowel and as consonant (i.e. like English W).

The letter F (Greek di-gamma) was used in Greek for consonant U (English W), but in Latin it was used to write the sound F, also a labial consonant, which did not exist in Greek.

In Latin, in the beginning 3 different letters were used to write the sound K, C before E or I, K before A and Q before O or U. So K belonged to the Latin alphabet since its very beginning.

Later, the rules for writing K have been simplified, so it was always written as C, except before a V (i.e. U sound) that was consonant, not vowel, i.e. like English W. Writing K has been retained only in a few traditional expressions, e.g. in "KALENDAE", which was used when writing dates.

Initially, the letter C (Greek gamma) was used both for the sound K and for the sound G. Later, the letter G has been created, by modifying the letter C. Since then, G was used for the sound G, except in a few traditional expressions, e.g. the name "Gaius" has continued to be written as "Caius", together with a few other traditional names.

The new letter G has substituted in the Latin alphabet the letter Z (Greek zeta), which was not used in Latin. Therefore the 21-letter Latin alphabet has become:

ABCDE FGHIK LMNOP QRSTV X

Several centuries later, during the Roman Empire, 2 additional Greek letters have been added at the end of the alphabet, so the 23-letter Latin alphabet was:

ABCDE FGHIK LMNOP QRSTV XYZ

The letter Z was reintroduced, but not in its original place, because it was contained in some borrowed Greek words. The same with Y. While both V and Y come from Greek u-psilon, by the time when Y has been added to the Latin alphabet it was pronounced as a vowel different from both Latin V and I, i.e. as a front rounded closed vowel, like the Scandinavian Y, German Ü (U with Umlaut) or French U.

The 23-letter Latin alphabet has become a 26-letter alphabet more than a millennium later, when the letters J, U and W have been added (J and U were required because in the Romance languages the old I consonant and U consonant had become fricative sounds, completely distinct from the I and U vowels, while W has been initially added for English, which is one of the few Indo-European languages that has retained the original pronunciation of consonant U).

>by the time when Y has been added to the Latin alphabet

Note also that the letter 'Y' is explicitly named 'Greek I' [literal translation] in Latin-descended languages; and then other languages borrowed that name (from the French).

It's not called that in English, of course, but English isn't a Latin-descended language.

Interestingly, the same is not true for 'Z', which is a more direct 'zed' (or 'zet', not like 'd' and 't' are that different) in most (all?) European languages, including the Germanic ones.

By ryao 2025-06-205:35 The pronunciation of Y in Latin is the pronunciation of I with rounded lips. That is probably the reason for the name.

By dragonwriter 2025-06-1916:21 > In the case of K, U, and W, those were borrowed from Greek, weren't they?

"W" was added originally by northern Germanic languages, including English, replacing the practice of writing the same sound with a doubled "u" or "v". Which explains both its appearance and its name in English and many other languages.

You can substitute S or K for certain pronunciations of the letter C (sykle), but that is not true in the case of CH.

By dagw 2025-06-1916:32 You could replace CH with another two letter combination. Swedish for example uses TJ for a sound that is quite close to the English CH.

By gwd 2025-06-1919:02 Chinese Pinyin use q for one of their two ch-like sounds -- we could do the same. Q is even more redundant than C, because not only is it identical to K, it's always followed by a U.

By madcaptenor 2025-06-1919:391 reply You could replace C occurring by itself (or where CK represents the /k/ sound) with either S or K and then replace CH with C.

By badc0ffee 2025-06-1922:14 Ceers!

By tdeck 2025-06-198:33 On the subject of C, folks may enjoy this video on the letter's history: https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=chpT0TzietQ

- Historically in writing, many accents come from letters written above or below, or there was an existing use of the same letter for distinct sounds, so it was natural to mark existing letters rather than create new ones out of whole cloth.

- The use of digraphs is frequently due to historical sound changes; first, certain sound combinations changed valence, but others do not. Then one rewrites with the digraphs with the other instances by analogy. Sometimes it comes from borrowing; for example the historical use of "ch" to denote the historic greek "chi", or aspirated chi sound, as in "chronograph"

- Finally, it is easier to modify a existing type, or arrange movable type, to include an accent rather than to create one from scratch.

By HelloNurse 2025-06-199:57 Altering letters with combining marks (often derived from other letters and not invented from scratch) is not only easier to learn than complete novel letters, but also consistent enough to allow learning by analogy: dieresis, grave accent, acute accent, tilde, macron and the like affect different phonemes in similar ways.

By senderista 2025-06-204:09 See Irish for some very unintuitive use of digraphs.

Written characters and sounds don't usually correspond because pronunciation drifts very quickly in time (even two consecutive generations might have noticeably different pronunciation), and in different directions in different locations, while rules of "proper writing" change rarely, usually as a result of people agreeing to change them in order to catch up to an apparent accumulated drift of pronunciation.

As I understand (in a simplified way), every once in a while (once in a few centuries) there's a major language reform to make written form reflect current pronunciation as much as possible, but already in 100—200 years people would start asking "why do we write not like we pronounce", until some political movement decides reforming orthography would promote their agenda. Then the cycle continues.

By Anarch157a 2025-06-1921:12 Some languages do it way more frequently. Take my native Portuguese. Brazil had 3 ortographic reforms in the 20th century, while Portugal had 5 in the same period, all before the "Ortographic Accord" of 1990, that unified ortography in both countries.

> Written characters and sounds don't usually correspond because pronunciation drifts very quickly in time

In space as well. Local accents can be quite variable. This alone dooms any “we should write words as we pronounce them” to fail unless every region has its own orthographic rules, which would be honestly terrible.

By mananaysiempre 2025-06-1915:13 Phonemic / morphological spelling is a thing (or rather a range of things). E.g. Belarusian is spelled phonetically, but Russian spelling is closer to phonemic—while the Belarusian standard could be used to spell the Moscow variety of Russian pretty painlessly, for those of Vologda or Ryazan it would be a downgrade. (This does not stop standardized textbooks or tests from only touching on spelling mistakes that are natural in Moscow, but that’s another story.)

By create-username 2025-06-198:221 reply People must come up with new characters because they lack their own script. You can either have a script adapted to your language, or make the best of what you’ve got.

English doesn’t. Bernard Shaw tried inventing new letters. I guess that changing the English alphabet os a slippery slope. If you make it as phonetic as the Latin script is meant to be, and with special characters, people would have to relearn how to read from scratch

If people followed the alphabetic principle for English, the written language would become unintelligible due to all of the regional variations in pronunciation causing there to be many variations of the same words.

By pessimizer 2025-06-1910:27 English has between 16 and 22 vowels (iirc) depending on the variety. English speakers that use a different set of vowels than each other often cannot understand each other at all at speed.

Color and colour are different pictures of the same word.

By jcranmer 2025-06-201:35 Ask people how many different vowels there are in this set of words: trap, bath, palm, lot, cloth, thought. Most English speakers will make out two-four vowels from those 6 words. But they won't agree on which words share the same vowels.

There are other phonological differences between English dialects, but for the most part you can notate them as sounds that merely some dialects don't distinguish (e.g., nonrhotic dialects dropping the `r' sound).

By t-3 2025-06-1913:33 That's not a pronunciation difference though. Almost all english dialects and regional accents pronounce that word very similarly. It's just an introduced spelling difference for aesthetics.

I (no expert, hopefully one will be along in a minute) have heard that in Swedish the letters äöå all evolved from corresponding diphthongs - so ae oe and ao respectively. Because the pronounciation changed from what one would assume from the literal spelling it made sense to create new letters to keep things consistent. They are considered to be entirely different letters by the way - much as you wouldn't consider O and Q to be the same letter with an accent.

In Swedish dictionaries those letters are added to the end of the alphabet - it's surprisingly hard to internalise that and remember to look up Å words at the end of the dictionary and not the front...

Edit: tokai below says Å was AA originally not AO so I (unsurprisingly) stand corrected: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=44317851

By mananaysiempre 2025-06-1914:351 reply The umlaut comes from an e written above the letter, and is thus historically distinct from the diaeresis aka tréma (as in Noël, naïve). I first realized after that looking at Fraktur street signs in Vienna, where it is more like two vertical lines, but the most immediate understanding will probably come after looking at the lowercase e in a table of Kurrentschrift[1].

Which, incidentally, is missing in TFA. Funny how thoroughly the Nazis managed to erase that piece of German legacy (and the only modern Latin-script cursive distinct not coming from the familliar Irish>Italian lineage).

Note the three Swedish characters åäö are not umlauts. This comment explains it well.

By NoMoreNicksLeft 2025-06-1913:412 reply Cyrillic has letters for both sh and ch. Greek has letters for both phonemes of th. Alphabets have alot of inertia after their initial foundation. That's why even when they make new letters they're almost always diacritics or ligatures. Hell, English did this with &, but we decided that it was punctuation instead of a new letter.

Completely off-topic, why the hell does Hangul's G look like a backwards Gamma? Is that coincidence, there's no way that was borrowed from the other side of the planet.

By andoando 2025-06-1921:45 Armenian has 39 characters. We distinguish between puh and pah, tuh and tah, zsh and zch, tsh and tch, etc

By mananaysiempre 2025-06-1915:07 > Cyrillic has letters for both sh and ch.

(With the one for sh, ш, having been borrowed from the Hebrew for sh/s/th, ש.)

And yet there have been some ligatures converted into letters following sound changes, as in ЪІ > Ы for [ɨ] (in Russian and Belarusian) or ІО > Ю for [ʉ] (in Bulgarian, Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian).

By bazoom42 2025-06-207:45 Characters like å and ø are considered distinct letters but they originated as diacritics. Diacritics are small symbols which can be added to existing text to remove ambiguities and aid in pronounciation. So the scripts started with the latin alphabet and then added various squiggles to the existing letters.

By dragonwriter 2025-06-1916:191 reply > Why do Ç, å, é, etc. exist? Why didn't people come up with new characters? Why use "sh" and "ch" instead of making a new character for those sounds? (Maybe other languages do this but English doesn't).

English doesn't? Explain "w".

By bazoom42 2025-06-2014:11 W is a ligature of “vv” which turned into a distict letter, similar to how “ae” turned into the letter æ. New letters in latin scripts seem to have evolved from either diacritics or ligatures. There are a few examples of letters borrowed from non-latin alphabets like þ in Old English

Å is a new character. It is not an a with an accent. It was created to replace the non letter aa.

But visually it's still an "A" with a "°" on top. Why not create an entirely new letter?

By qw 2025-06-2011:09 Originally, the "o" on top of the letter "Å" was a lower case "a", because the sound could be written as "AA". Over time it transformed into a circle.

Some names today still use the double a, like the Norwegian football player Martin Ødegaard. In that case it is pronounced the same as the "å" sound. (not too far from how an American might pronounce the "o" sound in "for")

Why is a Q just an O with a tail? Why is W just two Vs stuck together? These things are historical and seem normal now, and are hard to change.

By behnamoh 2025-06-1919:08 Good point! But it seems like diacritics and umlauts are an exception and people usually associate the underlying letter to letters that already exist in the alphabet.

By bazoom42 2025-06-2015:17 These letters have evolved over time. The latin letters ao was used for the sound but over time it became a ligature where the o moved on too of the a. Similar to how vv became w over time.

While some script are deliberately designed, most are a result of gradual evolution.

By kjkjadksj 2025-06-1917:27 Croatian has these as š or č/ć

Not sure if it's just my browser, but this just looks like a simple visualisation of which found texts where written in which style, when. It says absolutely nothing about the relationship and how the different strands evolved together, nor their locality.

Additionally, it counts modern font inventions as variants of the Latin Alphabet (a somewhat strange but acceptable interpretation) but then proceeds to not show its variants, despite the historic glyphs being shown in multiple variants each.

I find it lacking.

By rf15 2025-06-206:56 Turns out: in the end it was my phone browser that didn't show some of the connecting lines due to its Dark Mode Plugin. This is much cooler on Desktop!