In the AI era, the winners won’t be the tools you adapt to — they’ll be the tools that adapt to you. Let's take Linear. It is a beautiful, well-designed, simple but inflexible tool with little room…

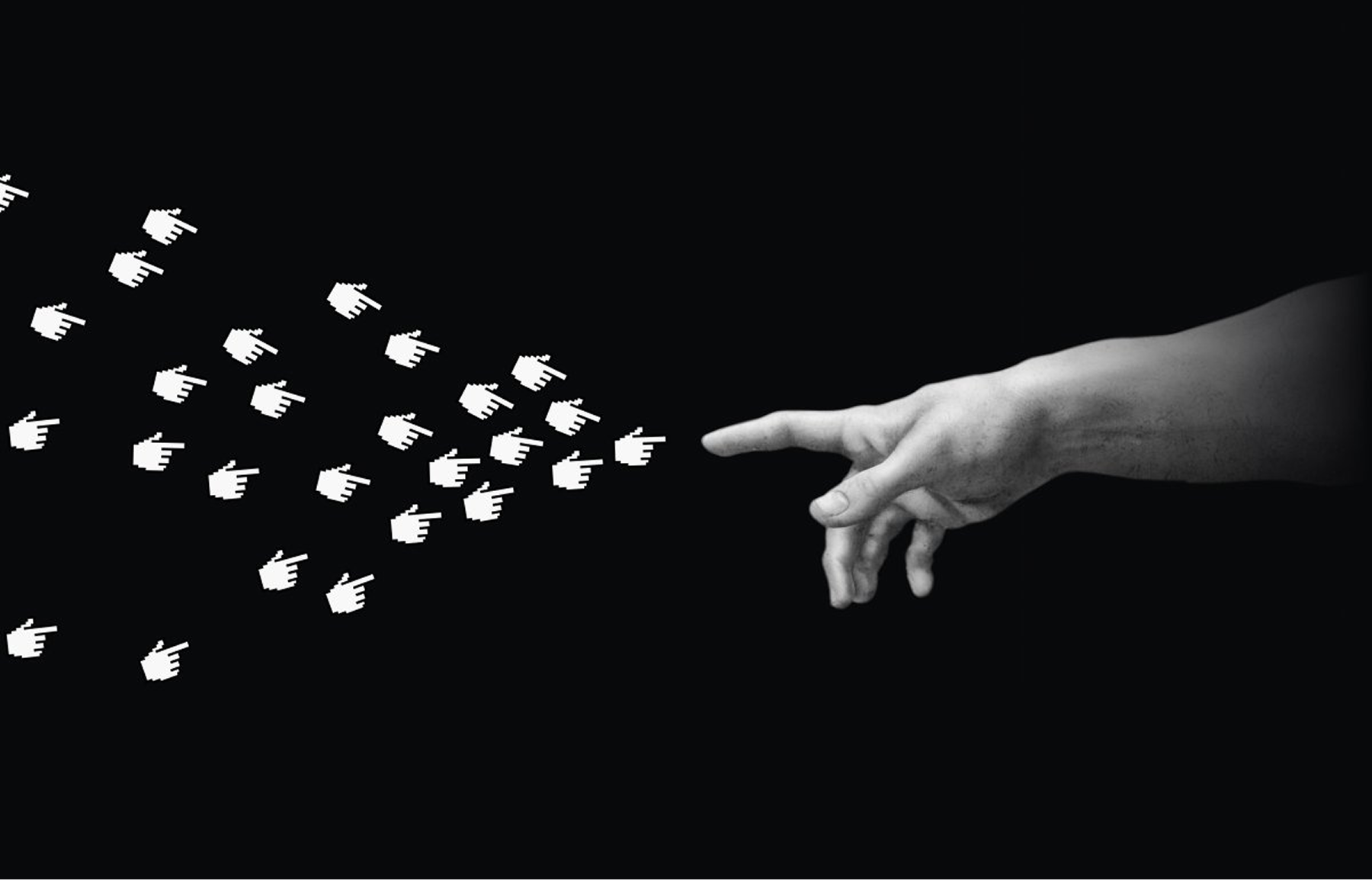

In the AI era, the winners won’t be the tools you adapt to — they’ll be the tools that adapt to you.

Let's take Linear. It is a beautiful, well-designed, simple but inflexible tool with little room for AI to add value. AI thrives in messy, open-ended spaces where it can design, assemble, and adapt — but in Linear, the major design choices have already been made. At best, AI might shave a few seconds off repetitive tasks or auto-fill a few fields, but it can’t reinvent the core process, because the tool doesn’t allow it.

Let's take Fibery. It is somewhat beautiful, quite well-designed, complex and flexible tool 😝. However, it is relatively hard to setup Fibery for your needs. LLMs turn complexity from a barrier into an advantage, collapsing weeks of setup into a few prompts. In a world where “how” disappears, the most adaptable tools will win.

Problem vs. Solution

The biggest shift LLMs bring to malleable software is moving the focus from designing the solution to defining the problem.

In the past, when you had a problem in mind (the what), you still had to figure out the how — which meant learning the tool, assembling components, and translating your needs into its language.

Now, in many cases, LLMs can handle the "how" for you. You describe what you want in plain language, and the system works like a programmer or system analyst: breaking your problem into building blocks, mapping a flow to solve it, and creating the first version. You review the result, give feedback, and iterate. The entry barrier drops dramatically, and the loop from idea to working prototype becomes fast.

Malleable software FTW

Historically, malleable software was a niche for tinkerers. It demanded time, patience, and a willingness to wrestle with complexity. Learning it took effort. Building with it was cognitively heavy.

That’s why simple, vertical solutions thrived. You picked something popular, used it as-is, and avoided customization altogether. Linear, for example, gives you a well-designed, opinionated process for software development. It’s a good process — but not the right one for everyone.

This changes when customization becomes fast and easy. If AI can bend a tool to your process in minutes, why settle for a rigid default? At some point, your needs will evolve, and with a locked-in tool, you’ll hit a wall. With malleable software, you just keep going and bend it to fit your new needs.

When you can have a tool shaped to your process in minutes, why would you accept one that shapes your process instead?

My take is that malleable software will replace less flexible hardcoded tools in some observable future. When configuration and setup is fast, easy (and fun), there is no way back to rigid tools.

This shift won’t happen overnight, but the trajectory can be like this:

2025–2027 – AI starts removing the steepest parts of the learning curve in malleable tools. Teams still pick rigid tools for speed, but migrations accelerate when processes evolve.

2028–2030 – The default buying question changes from “How fast can we start?” to “How easily can we change later?” Rigid tools lose ground in competitive evaluations.

2030–2035 – Malleable platforms, powered by AI assistants, reach a point where setup feels like a conversation, not a project. Switching costs collapse, and most rigid vertical SaaS tools become niche or legacy solutions.

Rigid tools won’t vanish completely — some industries will still prize absolute standardization over adaptability — but for most use cases, they’ll be relics of a pre-AI era.

The future belongs to software that bends without breaking.

P.S. HN thread if you feel like it.

Read the original article

Comments

By jaimebuelta 2025-08-2710:235 reply I see some of this, from the point of view that it's going to be cheaper to create bespoke solutions for problems. And perhaps a "neoSaaS" company is one that, from a very bare bones idea, can create your own implementation.

But, at the same time, there are two issues:

- Companies can be really complex. The "create a system and parametrise it" idea has been done before, and those parametrisation processes are pretty intensive and expensive. And the resulting project is not always to be guaranteed to be correct. Software development is a discovery process. The expensive part is way more in the discovery than in the writing the code.

- The best software around is the one that's opinionated. It doesn't fit all the use cases, but it presents you a way to operate that's consistent and forces you to think and operate in certain way. It guides you how to work and, once going downstream, they are a joy to work with. This requires a consistent product view and enforcing, knowing when to say "no" and what use cases not to cover, as they'll be detrimental from the experience. It's very difficult to create software like that, and trying to fit your use case I'll guarantee it won't happen.

These two things tension any creation of software, and I don't think they'll go away just because we have a magical tool that can code fast.

The best software around is Emacs. Does that count as "opinionated" in your view?

In some ways it is—Emacs does a lot of things its own way, completely unbothered by mainstream conventions—but, at the same time, it's also totally malleable in the sense of this article. What makes Emacs great is a consistent and coherent conceptual foundation coupled with remarkably flexible code, letting you adjust Emacs to your needs rather than adjusting your needs to Emacs.

Or maybe the best software around is situated software. Software that's built by and for a specific set of people in a specific social context. Situated software is qualitatively different from product software, and it works so well because, again, it gives its users real agency and control. Instead of trying to create software that knows better than its users, we can create software that supports its users in whatever ways works for me. The result is still opinionated, but it's opinionated in a categorically different way from what you're describing.

So perhaps the best mainstream software is Excel.

And, while I don't think they're there now, it seems like LLMs are likely to be the foundation for the next Excel.

By skydhash 2025-08-2716:13 You can either go with simple primitives and a way to combine them (emacs, excel, unix) or simple program that just works (notepad, sumatra,…). Anything else is going to be restrictive in one way or another.

By godelski 2025-08-2721:59 As a vim user I agree with all this. Same is true about why I am terminally terminal. I'm able to adapt the tools to me so that I may get the most use out of them. Sane defaults are great, but there are no settings which are universal. The only solution to this is to let people adjust as needed.

By osigurdson 2025-08-2714:182 reply I think the article presents a bit of an odd premise - I can make a mini app in ChatGPT today so by 2035 I can create an entire suite of software needed for a given business. What is the requisite change between what I can do now and in 2035? Presumably it is AGI.

OK, so we are in a digital super intelligence world in 2035. The HR department can now just have a conversation with a chatbot and create software to make them more productive. No more configuring SAP widgets or whatever they do today. The chatbot will be like "hey bro, the process that you want to automate doesn't make any sense: here is a better way. And, by the way, I'm terminating your entire department. I'll take care of it from now on". I mean, get real, in a post DGI world there will be exactly zero office jobs and no SaaS software at all.

By ozim 2025-08-2716:39 Odd premise is that AGI will have infinite bandwidth to deal with petty stuff like taking over menial stuff of HR departments.

Current AI barely keeps up with generating funny images people ask from it :)

It doesn't need to be AGI to build complex software. A human software developer can build a complex software system and perform other complex tasks with the same body (play an instrument, fly an aircraft, etc.). Doing all of that with the same resources is what AGI is needed for. Just software, well I'm sure an LLM can eventually become an expert just like it learnt how to play Go.

By osigurdson 2025-08-2714:331 reply AGI usually means "equivalent to human" while digital super intelligence generally means "smarter than all humans put together". In any case I agree that once we reach "equivalent to human" naturally it can do anything we do. That should be enough to end office jobs imo.

By 1718627440 2025-08-287:122 reply A machine, that is capable of performing human intelligence in every paradigm, according to a mathematical model, and scalable by increasing the frequency, power or duplicating it, because it is reproducible, is both "equivalent to human" and "smarter than all humans put together". When humans were capable of producing this, then this will be capable of improving itself and optimizing until the limit of information density. The only limit will be money as a proxy of available resources.

> scalable by increasing the frequency, power or duplicating it

Well there's your problem. Very few things scale like that. Two people are not twice as smart as one person, nor are two instances of ChatGPT are twice as smart as one. One instance of ChatGPT running twice as fast isn't significantly smarter, and in fact, ChatGPT can never outrun its own hallucinations no matter how fast you overclock it.

Intelligence is the most complex phenomenon in the universe. Why would it ever scale geometrically with anything?

> When humans were capable of producing this, then this will be capable of improving itself and optimizing until the limit of information density.

This doesn't follow. After all, humans are as smart as humans, and we can't really optimize ourselves beyond a superficial level (good nutrition, education, etc). Increasingly, AI is a black box. Assuming we do create a machine as smart as we are, why would it understand itself any better than we understand ourselves?

And why wouldn't we hit some sort of technical roadblock at (arbitrarily) 1.5x human intelligence? Why do we assume that every problem becomes tractable once a computer is solving it? Imagine we applied this reasoning to cars: Over a matter of a century, cars went from 10 km/h to 100km/h to 500km/h to (in special vehicles) 1000km/h. Can we expect to see a 5000km/h car within the next century? No, that's unlikely; at such high speeds, you begin to hit intractable technical limits. Why should scaling intelligence just be smooth sailing forever?

By 1718627440 2025-08-2818:261 reply > Very few things scale like that.

I wasn't talking about two instances for scaling smartness, I meant applying two instances to different problems. That very much scales.

> This doesn't follow. After all, humans are as smart as humans ...

In the hypothetical case of humans capable of producing the one true AI system (real AI or AGI or however its called, because marketing has taken the previous term), then this system is capable of producing another system by definition. Humans are capable of following Moores law, so this system will as well. So this chain of system will explore the set of all possible intelligent systems restricted only by resources. It isn't bound by inner problems like "(good nutrition, education, etc)", because it is a mathematical model, its physical representation does only matter as so far as it needs to exist in this hypothetical case.

> AI is a black box

In this case, the black box "humans" was able to produce another thing reproducing their intelligence. So we have understood ourselves better than we currently do.

Note, that every intelligent system is completely able to be simulated by a large enough non intelligent statistical system, so intelligence isn't inferable from a set of inputs -> outputs. It's really the same as with consciousness.

> And why wouldn't we hit some sort of technical roadblock? Can we expect to see a 5000km/h car?

Yes. We are capable of accelerating "objects" to 0.99..c. It's not impossible for us to accelerate a "car" to nearly light speed, we "just" need enough energy (meaning matter as energy).

> technical roadblock at (arbitrarily) 1.5x human intelligence

I wrote "until the limit of information density". Whatever this may be.

I intended to point out, why a system "equivalent to human" is actually equivalent to "digital super intelligence meaning 'smarter than all humans put together'".

---

You don't need to tell me you don't think this system will exist. I think this will end the same as the attempts to build a machine creating energy. My personal understanding is this: A system (humans) can never completely "understand" itself, because it's "information size" is as large as itself, but to contain something, it needs to be larger then this. In addition that "understanding" needs to be also included in its "information size" so the size to understand has at least doubled then. This means that the largest system capable of "understanding" itself has the size of 0.

In other words understanding something means knowing the whole thing and abstracting to a higher level then the abstractness of the system to be understood. But when the system tries to understand itself, it's always looking for yet another higher abstraction to infinity, as each abstraction it finds is not yet enough.

This idea comes from the fact, that you can't prove that every implementation of a mathematical model has some behaviour, without formalizing every possible model, in other words inventing another higher model, in other words abstracting.

> I meant applying two instances to different problems. That very much scales.

You can't double the speed at which you solve a problem by splitting it in two and assigning one person to each half. Fred Brooks wrote a whole book about how this doesn't scale.

> this system is capable of producing another system by definition

Yeah, humans can produce other humans too. We're talking about whether that system can produce an improved system, which isn't necessarily true. The design could easily be a local maximum with no room for improvement.

> Humans are capable of following Moores law

Not indefinitely. Technical limitations eventually cause us to hit a point of diminishing returns. Technological progress follows a sigmoid curve, not an exponential curve.

> It isn't bound by inner problems like "(good nutrition, education, etc)", because it is a mathematical model

It's an engineering problem, not a math problem. Transistors only get so small, memory access only gets so fast. There are practical limits to what we can do with information.

> We are capable of accelerating "objects" to 0.99..c.

Are we? In practice? Because it's one thing to say, "the laws of physics don't prohibit it," and quite another to do it with real machines in the real world.

> > technical roadblock at (arbitrarily) 1.5x human intelligence

> I wrote "until the limit of information density".

Yeah, I know: That's wildly optimistic, because it assumes technological progress goes on forever without ever getting stuck at local maxima. Who's to say that it doesn't require at least 300IQ of intelligence to come up with the paradigm shift required to build a 200IQ brain? That would mean machines are capped at 200IQ forever.

> Note, that every intelligent system is completely able to be simulated by a large enough non intelligent statistical system, so intelligence isn't inferable from a set of inputs -> outputs.

This is circular. If a non-intelligent statistical system is simulating intelligence, then it is an intelligent system. Intelligence is a thing that can be done, and it is doing it.

> A system (humans) can never completely "understand" itself, because it's "information size" is as large as itself, but to contain something, it needs to be larger then this.

I don't think this logic checks out. You can fit all the textbooks and documentation describing how a 1TB hard drive works on a 1TB hard drive with plenty of room to spare. Your idea feels intuitively true, but I don't see any reason why it should necessarily be true.

By 1718627440 2025-08-2912:271 reply > You can't double the speed

I only need two instances to be faster then a single one. This means the human having the resources to run the system is unbound to do anything an infinite number of humans can do regarding his own time and energy.

> Yeah, humans can produce other humans too

In this hypothetical scenario humans were able to build "AI" (including formalized, deterministic and reproducible). A system as capable as a human (=AI) is then able to produce many such systems.

> There are practical limits to what we can do with information.

Yes, but we are nowhere near this limits yet.

> Are we? In practice?

Yes. We are able to build a particle accelerator. Given enough resources, we can have enough particle generators as there are particles in a car.

> That would mean machines are capped at 200IQ forever.

Except when the 300IQ thing is found by chance. When the system is reproducible and you aren't bound by resources, then a small chance means nothing.

> This is circular.

No it just means intelligence is not attributable to a black box. We don't think other humans are intelligent solely by their behaviour, we conclude that they are similar then us and we have introspection into us.

> You can fit all the textbooks and documentation describing how a 1TB hard drive works on a 1TB hard drive with plenty of room to spare.

It's not about encoding the result of having understood. A human is very much capable of computing according to the nature of a human. It's about the process of understanding itself. The harddrive can store this, it can't create it. Try to build a machine that makes predictions about itself including the lowest level of itself. You won't get faster then time.

> Yes, but we are nowhere near this limits yet.

Says who?

> Given enough resources, we can have enough particle generators as there are particles in a car.

Given by whom? I said in practice—you can't just assume limitless resources.

> Except when the 300IQ thing is found by chance. When the system is reproducible and you aren't bound by resources, then a small chance means nothing.

We're bound by resources! Highly so! Stop trying to turn practical questions about what humans can actually accomplish into infinite-monkey-infinite-typewriter thought experiments.

> We don't think other humans are intelligent solely by their behaviour

I wouldn't say that, haha

> It's not about encoding the result of having understood. It's about the process of understanding itself.

A process can be encoded into data. Let's assume it takes X gigabytes to encode comprehension of how a hard drive array works. Since data storage does not grow significantly more complex with size (only physically larger), it stands to reason that an X-GB hard drive array can handily store the process for its own comprehension.

By 1718627440 2025-08-2921:531 reply > Says who?

Because I think we haven't even started. Where is the proof based system able to invent every possible thought paradigm of humans a priori? I think we are so far away from anything like this, we can't even describe the limits. Maybe we will never have and never do.

> you can't just assume limitless resources

I assumed that, because the resource limits of a very rich human (meaning for whom money is never the limit) and the one true AI system are not different in my opinion.

> comprehension

Comprehension is already the result. But I don't think this is a sound definable concept, so maybe I should stop defending this.

By bccdee 2025-08-3118:26 > Where is the proof based system able to invent every possible thought paradigm of humans a priori?

Beyond the realm of feasibility, I'd imagine. The gulf between what is theoretically possible and what is realistically doable is gargantuan.

> I assumed that, because the resource limits of a very rich human (meaning for whom money is never the limit)

The resources of a very rich human are extremely limited, in the grand scheme of things. They can only mobilize so much of the global economy, and even the entire global economy is only capable of doing so much. That's what I'm getting at: Just because there's some theoretical configuration of matter that would constitute a superintelligence, does not guarantee that humanity, collectively, is capable of producing it. Some things are just beyond us.

By osigurdson 2025-08-2823:42 I'd say it might scale like whatever your mathematical model is telling you, but it might not. I don't think we have a reasonable model for how human intelligence scales as the number of brains increases. Sometimes it feels more like attenuation than scaling in many meetings.

> The best software around is the one that's opinionated.

This. And it isn't going to change.

The post avoids trying to answer "Why are opinionated tools popular and effective?"

The answer is that a standardized process that they encourage is often more efficient than whatever bullshit {random company} came up with in-house.

Malleable software needs to produce two equivalently good outcomes to beat opinionated:

1. Improve the underlying process at the customer's business (in terms of effectiveness)

2. Avoid a customization maintenance burden

The seductiveness of "just for you" bespoke solutions is they avoid (1) by telling the customer what they want to hear: you're so brilliant, your process is actually better, our product is a custom fit for your exact process, etc. That's bullshit -- a lot of customer processes are half-baked dumpster fires, and their companies would be better served by following standards.

To (2), I am incredibly skeptical on the long-term tech debt that malleable solutions will impose. What happens when there's a bug in the version only you use? Is that going to be the vendor's priority? Oh, you're supposed to fix it yourself? Congrats... we've just added a requirement that these tools are capable of making random mid-level in-house practitioners as competent as focused dev teams. That's a tall order.

Exhibit A that I'd want a follow-up post to address: SAP.

The above are the reason they realized they were trending in the wrong direction and have been dragging their customer base back to Clean Core.

Walk me through how malleable software would work better for SAP as a product, and I'll begin to believe...

Highly customizable configuration causes all kinds of problems in healthcare, and EHR customizations have actually killed people.

By RUnconcerned 2025-08-2714:111 reply In my first job I had to work with healthcare software and it horrified me. There is a standard for interop, HL7, but every system implements HL7 in its own special way so there are "integration engines" to massage the data so that they all conform to the same standard.

It's a gigantic grift.

The history of HL7 is kind of nuts. It was originally developed for copper wire communication in 1979. Formalization was ongoing until maybe the early 1990s and lots of proprietary usage arose, because back in the 1990s none of these systems really inter-operated and everything eventually ended up on paper. It wasn't until after the ACA that a lot of interoperability pushes really got going at scale. Before that you had a few Health Information Exchanges at state levels so there was usually a local standard if there was an HIE. HL7 FHIR is much more standardized now.

I wouldn't call any of it a grift. It's just old tech built for a fragmented archipelago of systems that didn't communicate. Also you can write a pretty good HL7v2 parser in an afternoon, I've written maybe 5 of them.

The koan that unlocked why healthcare technology is the way it is for me:

I was working on automating health insurance claims processing on a mainframe system.

In their key interface, a key form had 8 blanks for ICD codes. If more than 8 codes were needed, a child claim was created and linked to the parent claim.

This was a long project, so I was staring at this interface for months, as linked child claims made automation more complex than it needed to be. (E.g. if a parent claim had aged, been archived, and needed to be reloaded to active overnight before processing the child claim)

Finally, I started asking around. "This is a computer system. Why are there a finite number of fields for something that might need more?"

Nobody knew. Project continued. I continued asking different people.

Finally, I asked a guy who had been working in the industry since the 1960s...

"Oh, because that's how many fields there were on the paper version of the form that preceded the mainframe app."

Which seems insane, until you think it through. There were innumerable downstream processes of that paper form.

Changing the number of fields on the digital version would have cascaded that change downstream to all those processes. In the interest of rapid implementation, the optimal approach was to preserve everything about the form.

And then nobody had a reason to go to the bother to change it for the next 50 years. (And that was a process within a single company!)

By 1718627440 2025-08-287:151 reply But you can split these claims into child claims upon printing. That's the thing with good software, the user model and the internal implementation are completely orthogonal. I think a good example of this is postfix.

By ch4s3 2025-08-2820:38 > But you can split these claims into child claims upon printing

Maybe, if business rules and the law allow a thing like that. If insurance won't pay claims like that then you can't do it.

By BinaryIgor 2025-08-2717:09 100%; customization maintenance burden is underrated - it simply costs a lot of time and energy to customize things; often there are better uses of this time, especially in the business context

Your arguments are totally valid, niche tools will be alive and well. I think my take is that even in niche tools we will see a lot of generalization and more flexible niche tools will eventually win.

By crote 2025-08-2713:49 The problem is that software can be too flexible. A great example is companies ending up using Excel as a load-bearing database, relying on a bunch of incomprehensible macros to execute critical business logic.

Sure, it's flexible, but are they really better off than a competitor using properly-engineered one-off software? In the end, is there really a difference between software development and flexible-tool-configuration?

By godelski 2025-08-2721:21

I think this is a great argument for flexible code, though it was unclear to me that the author of that post was talking about that.> Companies can be really complex

I think I might be on the same page as you but I would say that the best software is written to be an environment more than a specific tool. You're absolutely right that you can't solve all problems.> The best software around is the one that's opinionated.tikhonj jokingly suggests emacs but even as a vim user I fully agree. Like they say, the beauty of it is that the complexity draws from simpler foundations. It is written as an environment rather than just as a text editor. Being written that way lets it adapt to many different situations and is what has kept both vim and emacs alive and popular after all these years. There's a constant in software development: requirements change with time. The point of writing an environment is that you're able to adapt to these changes. So any time you write a tool that tool is built out of that environment. Anything short of that means the tool won't be able to adapt as time marches on.

I definitely agree that writing software like this is hard but I'm not sure if it is harder. It takes more work up front but I'd argue it takes less work in the long run. It's just that in the long run many efforts are distributed across different people and time. But hey, good flexible code also tends to be much easier to read and that's big short term benefit to anyone coming into a mature project.

For six years I worked in a SaaS startup that built an applicant tracking system (a tool to manage recruitment efforts in big/mid-sized companies) tailored for the local market of the country we lived in. My experience tells me that our main value was in forcing them to rethink their recruitment processes, not adapting to their existing ones that were usually all over the place.

As much as I want to believe the opposite to be true as a “power user”, good tools often force you to adopt better practices, not the other way around.

By lioeters 2025-08-2715:54 > good tools often force you to adopt better practices

Just wanted to highlight this excellent statement. It's like having a strict type system that enforces certain rules are always met. It provides consistency and predictability.

> rethink their recruitment processes

This context is relevant to the kind of software system that was needed. To improve their processes, it was necessary to impose an explicit top-down order to the existing mess.

Malleable software, on the other hand, feels more suited for personal computing, greenfield projects, or small teams with members working independently as well as collaboratively. Particularly in the early stages of product R&D, strict rules can be a source of friction in the creative process.

Strict better practices and well-designed tools are discovered and developed through open and flexible explorations, as a kind of distillation of knowledge and experience.

By sarchertech 2025-08-2710:47 I worked for a company that provided a mobile friendly job application form that integrated with major applicant tracking systems (back when they didn’t provide mobile friendly forms).

Our biggest value was getting customers to remove all the extra questions on their applications that had built up over years of management changes that no one had any idea why they were even asking.

The problem here is in definition. Context is quite diverse and better practice for team A is an absolute disaster for team B.

By cyco130 2025-08-2710:16 Absolutely. When we started growing (I was employee #3, we were about 20 people when I left), we didn't use our own product for our own needs. It wasn't designed for a tiny startup, it would be like building a sand castle with a bulldozer.

But we started as a "boutique" company that implemented everything requested by our then small number of clients (mainly out of desperation, we were self-funded and we didn't have much leeway, we needed those clients). It was as flexible as it gets before the LLM times.

But after a while, you start noticing patterns, an understanding of what works and what doesn't in a given context. Our later customers rarely requested a feature that we didn't already have or we didn't have a better alternative of. It's not like we had a one-size-fits-all solution that we forced on everyone. We offered a few alternative ways of working that fit different contexts (hiring an airline pilot is a very different context than hiring a flight attendant). And in time, this know-how started to become our most important value proposition.

At some point we even started joking about leaving the software business and offering recruitment consulting services instead.

By cyco130 2025-08-2710:26 In fewer words: It was already a fairly flexible and customizable tool. But then came a time when a client requested faster horses we could show them our car instead and they recognized the value. (And occasionally, when _they_ requested a car instead of our faster horses, _we_ recognized the value and implemented it).

By flappyeagle 2025-08-2812:47 They should use different tools then.

Malleable software enables infinite variations of tools when the correct number is in the single digits.

A lot of people been saying this lately, that LLMs are going to make SaaS obsolete because you will be able to build the alternative yourself without the need to pay.

But (and I'll copy & paste a comment I wrote a few days ago) I disagree. This existed way before LLM. Open source alternatives to most products are already available. And install them and deploy them is much easier than do it with LLMs, and you get updates, etc.

People don't want the responsability to keep them updated, secured, deployed, etc. Paying a small amount will always be more convenient than to maintain it yourself. The issue was never coding it.

Counter argument: people want simple systems that are easy to update, secure, deploy etc. I've been burned so many times by being an early adopter of a simple product for it to add too many features and shifting focus along the way, leaving the early adopters as second class users. This usually happens because investors wants a return on their investment by enshittifying the product.

As self hosting with Docker and getting help from LLMs gets easier I can totally see a future where more companies self host. Having to deal with SaaS companies also takes a lot of time (licenses, hidden limits you can reach at any time, more complex privacy policy, approval from management), especially as they usually end up selling after a couple of years. The responsibility to self host isn't that bad all things considered.

I don't think we'll see companies vibe code the replacement of their software, but it might help them self host open source alternatives.

What percentage of companies do you think have the technical know how to even fire up their own cloud application and database instance even with all the LLM assistance in the world? Outside of companies in the software space and some of the largest orgs, I’m gonna guess maybe 20%?

By zOneLetter 2025-08-2713:17 Don't forget the audits and compliance reports. No company with a C-suite with more than 3 brain cells combined will be going down that route. People forget that hobby-projects do not have the same legal and business requirements as ... enterprise projects.

By bryanrasmussen 2025-08-279:451 reply hey yeah, there's no need to have a payment provider to take care of all your taxes being paid correctly and on time. We have AI!

This would be one of the greatest entertainment events of the 21st century! Shame about all the destruction that will happen as a consequence of course, but ...entertainment!

By actionfromafar 2025-08-279:491 reply Whole governments run in that mode now.

By bryanrasmussen 2025-08-279:591 reply Our Governments AI says we never paid our taxes, Our AI says it paid our taxes, our CEO says nobody should pay taxes, and our VC's AI says we're broke and a Unicorn at the same time.

By javcasas 2025-08-2713:28 Yup, that should be recorded and shown in Netflix. Pure entertainment.

Now put all these actors in the same room with a bomb, tell them to agree on the situation of the taxes or the bomb explodes, and you have one hell of a drama.

This is not what the article is about. Main idea is that rigid software can finally be replaced by flexible, since flexibility is no longer such expensive

Nope, anyone saying this does not understand fundamentally what software is. This so-called malleable software is a recipe for chaos.

By 87553530896046 2025-08-2710:06 Not everyone can be as enlightened as gurus like you.