A century ago, these were the cars on Britain’s roads. Forget driving lessons or tests; to get behind the wheel legally, all you needed was a paper license, which cost the equivalent of around 25 pence today.

Cars had no seatbelts and, of course, no airbags. There were no mirrors to let you see traffic behind. There were no flashing indicators, so your signal to turn left or right was simply sticking your arm out. The brakes were poor, and emergency braking was impossible. Steering was stiff and clunky, and the headlights were weak, making it difficult to see much at night.

Combine this with the lack of pavements for pedestrians, the lack of signs or traffic signals, and the absence of enforced rules, and you can understand why it was a dangerous time to be on the roads.

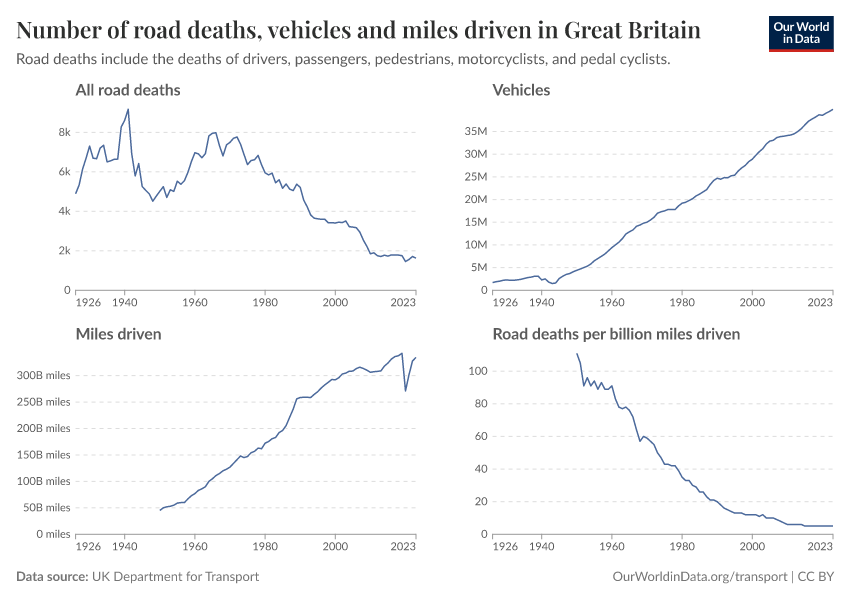

Throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, between 5,000 and 7,000 people died in road accidents each year.

Fast-forward to today. Around 1,700 people die in road incidents each year in the UK: about a quarter of what it used to be, despite there being 16 times more vehicles on the road and 33 times as many miles driven.

Per mile driven, the death rate declined 22-fold since 1950.

You can see all of this in the chart below.

If road deaths per mile driven were still as high as in 1950, then the UK would not see 1,700 road deaths per year, but 37,000.1

Today, the United Kingdom has some of the lowest road death rates in the world.2 You can see it compared to other countries in the chart.

How did road traffic become so safe in the UK? In this article, I want to journey through the history of policies, norms, and transport innovations that have saved thousands of lives yearly. These lessons help identify what works and what doesn’t, so that other parts of the world can make their roads much safer. Globally, around 1.2 million people die in road accidents every year. Yet this is one of the world’s most overlooked health problems, even though we already know how to prevent many of these deaths.

Many of the UK’s interventions and policies are reflected in the more general guidance in reports such as those published by the World Bank’s Global Road Safety Facility.3 These reports take a more in-depth look at the policies and interventions that are effective (or not) in reducing road fatalities. They align closely with the lessons I have drawn from Britain’s history.

Anarchy and blackouts: Britain’s roads until the end of World War II

Let’s go back to the period before the Second World War.

Speed limits on Britain’s roads had existed since the early 1900s, but they were rarely enforced, so hardly anyone followed them. In 1930, the government decided that speed limits should be abolished if no one was willing to follow them. The country’s own transport minister, Herbert Morrison, even admitted to ignoring them in parliament:

“… there was not one of their Lordships who observed the speed limit [and] I venture to say that as legislators we are not entitled to enforce and to continue speed limits.”

Just four years later, following concerns about the number of pedestrians killed on busy urban roads, a limit of 30 miles per hour was reintroduced in built-up areas. Road deaths stayed relatively stable throughout the 1930s until the start of the Second World War.

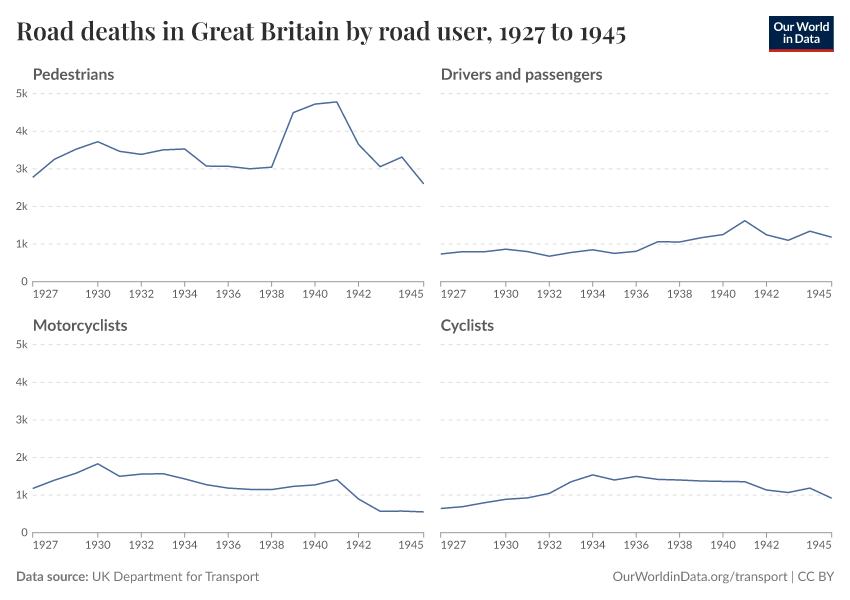

During the first few years of the war, road deaths increased. Mandatory nighttime blackouts prevented cars from using their headlights, and streetlights were turned off completely. The chart shows that pedestrians, especially, were paying with their lives.

As the King’s Surgeon wrote in the British Medical Journal in 1939:

“frightening the nation into blackout regulations, the Luftwaffe was able to kill 600 British citizens a month without ever taking to the air”.

The high risk to pedestrians in the first half of the 20th century was not only true in the UK. The Literary Digest was a weekly magazine in the United States; in the 1920s to 1940s, the humor section often featured jokes about how dangerous cars were to pedestrians.

Here’s one published in the Nashville Banner:

“With so many automobiles, the supply of pedestrians will soon be much short of the demand.”

And another:

TRAFFIC COP: “Hey you! Didn’t you hear me yelling for you to stop?”

AUTO FIEND: “Oh! Was that you yelling? I thought that was just somebody I had run over.”

Cars were becoming increasingly popular, but at the cost of those walking alongside them.

The climb to a post-war peak in the mid-1960s

Over the next few decades, road deaths steadily climbed to their post-war peak in 1966.

But it’d be wrong to conclude that the UK government did little to improve road safety at that time. Fatality rates declined, but this was not enough to offset the rapid rise in the number of cars on the roads and the number of miles being driven.

The chart below shows the change in each indicator from 1950 to 1966: the number of registered vehicles almost tripled, miles driven more than doubled, and deaths increased by just over 50%. That means rates actually went down.

What were some of the policies that successfully limited the number of deaths?

In the footnote, I’ll list a few small interventions for which there is mixed evidence, and instead focus on the larger ones with a more substantial evidence base.4

One of the most important changes during this period was the introduction of motorways (also known as “highways”). Previously, I’d have assumed that motorways were more dangerous than city or other rural roads, because cars drive much faster.

But it’s the opposite. You can see this in the most recent data for the UK, shown in the chart below. If we look at the number of deaths per billion miles driven, we see that motorways are roughly four times safer than urban roads, and more than five times safer than rural roads. This is not specific to the UK: among 24 OECD countries, approximately 5% of road deaths occurred on motorways.5 In almost all countries, it was less than 10%.

Rural roads are the most dangerous. In 18 countries, more than half of deaths occurred on rural roads, and it was more than two-thirds in Spain, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, and New Zealand.

Motorways are safer for several reasons. First, there are fewer road users — just cars, no pedestrians or cyclists. Second, there are fewer stops and starts. Third, there are usually physical barriers in the middle, separating vehicles traveling in different directions and reducing the risk of head-on collisions, which are much more common on narrow rural roads.

One key to road safety is having well-designed motorway infrastructure. The first motorway in the UK opened in 1958, and the growth of the network since then has saved many lives.

If motorways were the big infrastructural change of the 1950s, roundabouts were the innovation of the 1960s. In 1966, the UK government implemented the “priority rule”, which requires drivers at roundabouts to give priority to vehicles already in the roundabout. This rule continues to this day.

Again, I previously underestimated the importance of roundabouts because I assumed that the high and constant traffic flow might increase the risk of collisions. However, there is good evidence that well-designed roundabout systems make our roads much safer than the alternatives: intersections with stop signs (2-way or 4-way) and traffic light systems.

Studies have found that replacing traditional intersections with roundabouts substantially reduces injuries and deaths from collisions. The magnitude of reduction depends on the context and road conditions beforehand. A study in the US found that the conversion of 24 intersections to roundabouts reduced the number of injury crashes by 76%.6 In Europe, studies have found a 35% to 40% reduction in rates of serious injury crashes, and a reduction in deaths of 50% to 70%.7 A meta-analysis across 44 studies found that converting junctions to roundabouts was associated with a two-thirds reduction of fatal accidents.8

Again, roundabouts are safer for several reasons.

The risk of a side-on or head-on collision is much higher at traffic lights and stop sign interventions. These collisions tend to be much more dangerous and lead to higher fatality rates. On a roundabout, a collision will likely be at a much less severe angle, and head-on collisions are much rarer. Vehicles also tend to travel at higher speeds, especially at traffic light intersections, whereas effective roundabouts force vehicles to slow down. For this reason, roundabouts that are small and do not force cars to drive around them are ineffective because they can effectively drive right through, without slowing down.

Stop-sign intersections — especially 4-way ones — can cause confusion about which vehicles have right-of-way. Finally, both of these road designs force many stop-and-go movements, increasing the likelihood of crashes when drivers brake too late. Roundabouts allow a more continuous flow of traffic.9

While roundabouts reduce risks for drivers, passengers, and pedestrians, the data for cyclists is less clear. There is some evidence that large multi-lane roundabouts actually increase risks compared to traffic light intersections.

The battle against drunk driving

The other major change instigated in the late 1960s was the war against drunk driving.10

Those rates would be unthinkable in Britain today. That’s not just because of the legal ramifications: it’s also no longer socially acceptable to drink and drive. More than 90% of Brits say that drink-driving is unacceptable, and they’d feel ashamed if they got caught.

In a large survey of road users across Europe, around 10% of car drivers in the UK said that they had driven after having at least one drink in the last month. 8% said they drove while being over the legal limit. So drink-driving still happens, but it’s much less normalized than it used to be.

This shift happened through legal actions and public education campaigns.11 In 1967, the UK introduced a drink-driving law, which set an objective and measurable limit for how much alcohol was allowed in someone’s bloodstream. They also introduced breathalyzers and told police to stop and test people liberally. Before 1967, there was a law against drink-driving, but it was vague and hard to enforce. It was illegal to be "under the influence of drink or drugs to such an extent as to be incapable of having proper control of the vehicle", but without a legal limit or standardized testing, police often struggled to prove that someone was impaired due to alcohol, especially in court. This is a clear example of better data measurement having saved many lives.

Over time, the consequences for getting caught increased, including a permanent driving ban, hefty fines, or even jail time for serious offenses.

While the legal consequences were ramping up, the government launched hard-hitting ad campaigns to highlight the suffering that could be caused by drunk driving. Slogans such as “drinking and driving wrecks lives” became well-known. Advertisements where a night out ended with someone’s loved ones being killed increased the stigma of prioritizing one more drink over a person’s life. The evidence suggests that public information campaigns alone produce mixed (and often unimpressive) results, but they can make a real difference when paired with strong enforcement.

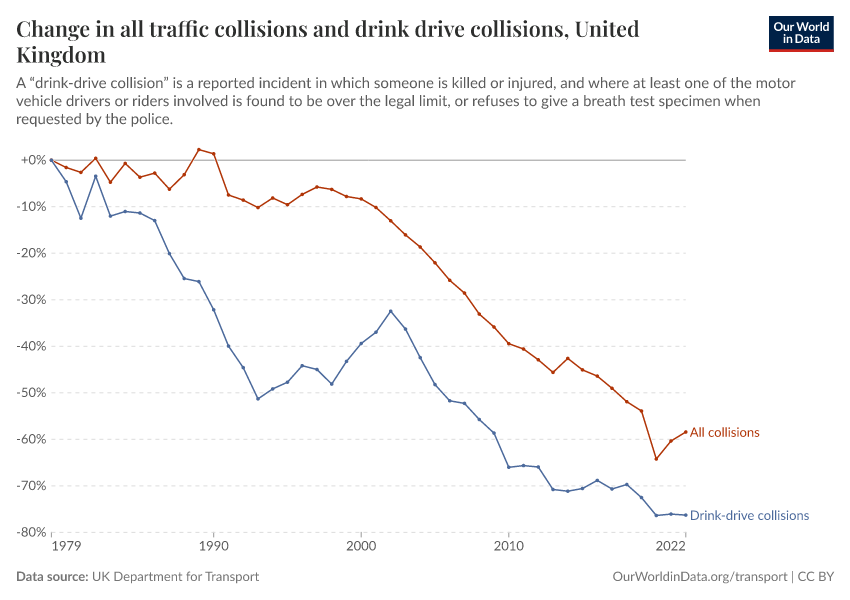

This battle has been incredibly successful. In 1967, 1,640 people died in drunk-driving incidents. This has fallen by 82% to roughly 300 per year. As you can see in the chart below, collisions involving drunk drivers have fallen even more quickly than the overall reduction in road collisions.

This reduction matters a lot because drink-driving incidents are particularly fatal. In 2022, just 4% of road collisions involved drunk drivers, but these incidents resulted in 18% of road deaths.12

The rise of motorcycle helmets, seatbelts, and safer cars

Tackling drunk driving helped to reduce the number of collisions, but much of the drop in deaths during the 1980s and 1990s was about protecting drivers and passengers when a vehicle did crash.

This rise in protection within cars was pre-dated by mandatory helmets on motorcycles in 1973. At the time, early data suggested that wearing a helmet dramatically reduced the likelihood of a serious or life-threatening head injury in a motorcycle incident. In the decades since, the evidence for this has only gotten stronger.13 In the US, states with less stringent helmet laws have more head injuries.14 A meta-analysis of studies across Africa suggests that helmet-wearing reduced the risk of a severe head injury by up to 88%.15

A decade later, in 1983, wearing seatbelts in the front seats of vehicles became mandatory. A few years later, belts became mandatory for children in the back seats, and by 1991, it was mandatory for everyone in the car. Like motorcycle helmets, seatbelts make a huge difference to someone’s odds of surviving a crash.16

But it wasn’t just the provision of seatbelts that changed. By the late 1990s, the European New Car Assessment Programme (NCAP) was introduced, spearheaded by the UK. It provided detailed safety assessments and tests for new cars. This programme was voluntary, but vehicles could receive a “safety rating” depending on how well drivers, passengers, and children would be protected during tests such as front-on and side collisions. This meant that people now factored in the safety rating of cars when choosing a new one, and manufacturers had to develop safer cars. Tests also showed the effectiveness of airbags, seatbelts, and “crumple zones” — the parts that absorb energy during a collision to protect occupants.

These innovations made a real difference to the odds that someone would survive a crash. It was during the 1990s and early 2000s that the number of deaths among drivers and passengers fell particularly strongly.

Making roads safer for kids: stricter speed limits and traffic-calmed zones

The most dramatic decline has been the reduction in the number of pedestrians killed on Britain’s roads. Since 1990, pedestrian deaths have fallen by 75% from around 1,600 to 400 per year.

Speed limits have played an incredibly important role, not just for pedestrians on urban roads but for all road users. As the World Bank’s report puts it:

“[...] there are no other risk factors that have such a substantial and pervasive impact on safety as speed. Speed has an impact on both the likelihood of a crash occurring, and severity of the outcome when crashes do occur.”

The relationship between speed and health impacts follows a “power law”: a 5% increase in average speed typically leads to a 10% increase in injury, and a 20% increase in deaths.17

Speed limits should be set based on the most vulnerable road users. They can be higher on motorways because everyone is protected within a vehicle. On urban roads, limits need to be set based on the risks to pedestrians and cyclists. In areas with many children, their vulnerability calls for even stricter limits.

In the late 1990s, the UK introduced 20-mile-per-hour zones around schools. These expanded throughout the 2000s and are now common across the country. Across the board, the enforcement of speed limits has become much tighter. These interventions can be very effective.18 If a pedestrian is hit by a vehicle at or below 20 miles per hour, they have a good chance of surviving. Above this, their chances fall dramatically. A study across 40 cities in Europe found that a 20-mph speed limit reduced the rate of fatalities by 37%.19 In some areas, including cities in the UK, it was as much as 70%.20

Like the war against drunk driving, these legal limits were also accompanied by emotionally visceral public campaigns. I still remember the TV advert I saw several times a week as a child. It featured a young girl, dead at the side of the road, with her voiceover telling drivers: “If you hit me at 40 miles per hour, there’s an 80% chance I’ll die. Hit me at 30, and there’s an 80% chance I’ll live”. These are the types of messages that stay with people and can change behaviors and attitudes.

As a consequence, the drop in child deaths on the UK’s roads has been dramatic. You can see this in the chart below. In 1980, over 600 children were killed. By 2021, this had fallen to less than 50.

Every year, about 1.2 million die on the world’s roads — we know how to bring this number down

A lot has changed since the first British drivers got their cars in the 1920s. The roads are different. The vehicles are different. People’s attitudes to driving are different.

These changes transformed Britain’s roads from chaotic to some of the safest in the world, saving thousands of lives every year.

Worldwide, around 1.2 million people die from road injuries every year. Most of them are in low- and middle-income countries, with much higher road death rates. If every country could lower its rates to those of the UK, Sweden, or Norway, this number would be just under 200,000.21 We’d save one million lives every year.

Learning from the history of how roads became safer would make a massive difference to people's health worldwide. It would mean that hundreds of thousands of parents, children, or partners don’t have to receive the dreaded phone call that their loved one will never come home.

Many thanks to Max Roser, Saloni Dattani, and Edouard Mathieu for their valuable suggestions and feedback on this article.

Continue reading on Our World in Data

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie (2025) - “How Britain built some of the world’s safest roads” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/britain-safest-roads-history' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-britain-safest-roads-history,

author = {Hannah Ritchie},

title = {How Britain built some of the world’s safest roads},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/britain-safest-roads-history}

}All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.